Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Tuesday, December 30, 2008

2008 Top Ten

In the grand tradition of year end top-ten lists, here's the top ten most clicked-on and linked posts of this blog for 2008. That's no matter when they were posted, by the way, and of course it doesn't count all the people that read posts directly on the front page. The list is tilted towards posts suitable for linking and forwarding, in other words, and posts that are easily found via Google and other search engines.

There it is: one vaguely sciency post, two posts on photography, three on Japanese society, three on food and one on language. Sounds about right for this blog.

- Handy Box (October 2008)

The Handy Box, an old Swedish-made box camera, with my impressions and sample pictures. - Stirling Engline (May 2008)

I show off a Stirling engine model I got and give a short overview of what a Stirling engine is, how they work and why they're just insanely cool. - Cup Noodle Museum (March 2008)

A visit to the Nissin Cup Noodle museum in Osaka. See the history of Cup Ramen, eat a wide variety of instant noodles and make your own, personalized Cup Noodle. Fun place.

- Voigtländer Bessa (October 2008)

The Voigtländer Bessa is another old camera from the 1950's I've been using lately. This one was owned by my uncle, originally, and is still perfectly usable. - Osaka Population (April 2008)

A look at population trends in Osaka prefecture. With illustrations! - Oyakodon Recipe (June 2008)

A simple recipe for Oyakodon, posted while we were in Sweden and Finland on holiday.

- Learn Japanese, Get a Visa (January 2008)

Where I described an upcoming plan to make it easier to get a work visa for applicants with demonstrated Japanese ability. It seems the plans continue apace and may be reality around 2011 or so. The JLPT language test is already changing in preparation for this. - Clam Miso Soup (June 2008)

A recipe for a very simple clam miso soup. Posted while traveling. Maybe I should post more recipes here. - Population Decline (November 2007)

A look at reasons for the declining population of Japan. It's part two of a three-part post; Part 1 and Part 3 here. - JLPT 1 (December 2008)

where I tell about my recent attempt and failure at the Japanese Language Proficiency Test level 1. Nobody's perfect.

There it is: one vaguely sciency post, two posts on photography, three on Japanese society, three on food and one on language. Sounds about right for this blog.

Sunday, December 28, 2008

One in Three Stolen Cars Not

Beginning of the holidays and amazingly life manages to become more, not less, hectic. Anyway, a recent nugget of news from a Swedish paper is worth a break: One car in three reported stolen during December is actually not stolen at all (in Swedish).

People forget where they parked, or they mistakenly think they took the car when they didn't, and when they can't find their car they report it stolen. This happens throughout the year, but is especially common during christmas season. Large parking lots, lots of identical-looking cars, and the stress of the upcoming holidays all contribute. I'm not immune myself; I've thought my bicycle has been stolen more than once when I simply couldn't remember where I parked it.

People forget where they parked, or they mistakenly think they took the car when they didn't, and when they can't find their car they report it stolen. This happens throughout the year, but is especially common during christmas season. Large parking lots, lots of identical-looking cars, and the stress of the upcoming holidays all contribute. I'm not immune myself; I've thought my bicycle has been stolen more than once when I simply couldn't remember where I parked it.

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

Merry Christmas

Traditional Japanese Christmas fried chicken.

Really, it's no stranger than any of all the other odd foods eaten in various countries during Christmas. Many countries have turkey or pork - in Sweden it's a whole ham, eaten over several days. They eat goose in Germany, green cabbage and eel in southern Sweden while Finns and Russians eat pirogs. And fried chicken is certainly preferable to the lutfisk eaten - for reasons unknown to science - in Norway and northern Sweden.

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

When Poodle Groomers Go Bad

Below a sample picture set of a poodle that has been boldly groomed where no poodle has been groomed before:

Creative Grooming Awards

I'm especially impressed by the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle one:

Of course, it doesn't hurt the dog in any way (yes, that really is a dog) and they don't have any sense of looking silly or anything. But really, this woman needs to take up sculpture or something.

Creative Grooming Awards

I'm especially impressed by the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle one:

Of course, it doesn't hurt the dog in any way (yes, that really is a dog) and they don't have any sense of looking silly or anything. But really, this woman needs to take up sculpture or something.

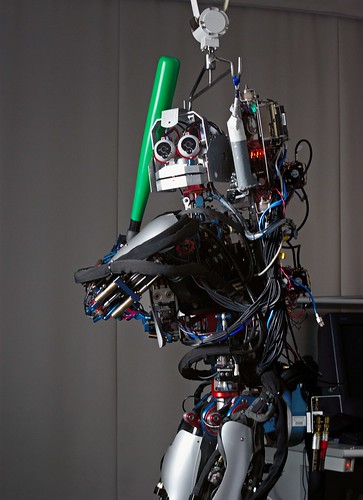

Automation

From Slate, an interesting take on the automation of manufacturing. While people in the US (and Japan) worry a lot about the outsourcing of the manufacturing base and the resulting loss of jobs, a surprising amount of work today is automated, not outsourced.

Automation has a long history and it's easy to lose sight of just how much it has changed the workplace over the years. Early in the industrial era nuts and bolts were actually made one by one, turned by a skilled machinist, and matched to each other so you'd have parts that fit. As late as mid last century companies maintained typing pools where skilled women neatly typed out documents based on handwritten notes. Not that long ago "Calculator" was still a job title, rather than a counting machine.

Automation has a long history and it's easy to lose sight of just how much it has changed the workplace over the years. Early in the industrial era nuts and bolts were actually made one by one, turned by a skilled machinist, and matched to each other so you'd have parts that fit. As late as mid last century companies maintained typing pools where skilled women neatly typed out documents based on handwritten notes. Not that long ago "Calculator" was still a job title, rather than a counting machine.

We have been losing work - production and service jobs alike - to machines for centuries already. This has periodically flared up as a hot-button issue, last time in the 1980's when there was a lot of fear that industrial robots and computers would cause permanent mass unemployment. Suddenly, though, the issue seemed to vanish. Industrial robots of the era were large, expensive and complex and unsuitable in most factory settings, and office automation created lots of new jobs and business opportunities that soaked up people even as old office professions disappeared. When opening markets and improved communications created an outsourcing boom in the 1990's, any thoughts of machines competing with humans were forgotten.

Outsourcing - specifically, outsourcing to emerging countries like China, India, Vietnam, eastern Europe and so on - is not a new phenomenon either. For well-to-do families in northern Europe a set of china (sic) with the family monogram and illustrations, commissioned and imported from China, was the very thing to have in the 1700's. The recent boom is probably noteworthy mostly because this time the driver is cost and because of the large number of industries involved more than anything else.

This trend to outsource is not permanent. It is arbitraging the wage differences between industrialized and emerging markets, but over time those differences are lessening and mostly remove any simple cost-related reasons to outsource production. This is overall a good thing; a huge amount of people in emerging markets are pulling theselves out of poverty. While the wage differential may have been the prime driver this time around, other reasons to outsource to other countries are as valid as ever so some outsourcing will persist no matter what. Some people hope that as costs rise - from wage level increases, transportation costs or import duties - that production will return to the industrialized countries. The production may well return, but the jobs, by and large, will not.

Outsourcing is really only a side show - a dress rehersal if you will. Many tasks today are done manually not because we can't automate them, but simply because a machine that can do it is still more expensive than a human, and especially a poorly paid human in a third-world sweatshop. The spread of automation did not stop, as the article shows, it just slowed when it had to compete with some very low production costs in the emerging world. But robotics and information technology continues to become cheaper and more capable even as salary levels increase. A shirt that once was sewn in France or England is now being sewn in Vietnam or Bangladesh, but will at some point in the future be made by a sewing robot. And where that robot is located will no longer really matter as far as sewing, cutting and trimming jobs are concerned.

The range of professions being touched by automation is increasing. Far from big, dumb metal arms doing repetitive welding or painting, industrial robots are very capable machines already, and the possibility exists for far more autonomous, resourceful systems that can handle very complicated tasks without supervision or detailed instructions. Again, to a fair degree it is already a matter of cost rather than ability. Imagine a sewing robot that can take shirt design CAD files - perhaps measured for a particular customer - a pile of cloth and by itself sort out the materials, cut the cloth, sew the panels, and add all trimming. The next week it'll do jeans. The next week in turn a special order for a boat sail, and all without any explicit programming or expensive reconfiguration. If there's too much work, just add another unit on the factory floor. If business is slow, just idle a few of them - or rent them to another producer - until things pick up again.

The rise of very capable dataprocessing and communication is changing service jobs in the same way. In Sweden, economic information about your wage, loans, real estate ownership, capital transactions and so forth is submitted by employers and banks, and is complete enough that for most people the tax office can prefill and precalculate most of your taxes automatically, including deductions and benefits. The tax code is as complex as ever, but whereas we all had to manually figure it out one by one, the tax office now has enough computing power and know-how to easily encode the very complex rules and regulations and apply them for the inhabitants of the entire country over the span of a few weeks, and improvements in communications technology and standards mean the tax office now has the data needed to do those calculations directly. This capability really is new, and it really is significant. After all, much of the complexity and anxiety of doing your taxes was to figure out which rule to apply when and how to go about it. That complexity is now automated.

The remaining job of checking the data and adding any additional info is now very easy - easy enough that most people need no help or further instruction at all. Very convenient, a big money and time saver for people and the tax office alike, and a major yearly stress moment gone for a lot of people. But it also destroyed the whole individual market for accountants and tax lawyers, how-to books and tax preparation software. Sure, a few people still need or want tax assistance but it's become a purely high-end boutique service, not a mass market. Automation has removed a class of service jobs, in other words, and not a low-end kind of work either.

So, disaster for humanity then? No. As I've written above, this is a very old trend, and we have seen this played out several times before. Once upon a time, the vast majority of people where more or less directly involved in agriculture and fishery while today only a small percentage are, even as production improvements mean the yield is much higher than ever before. But that never gave rise to 80% unemployment, as changes were slow and people adapted. Our streets are notably empty of roving gangs of feral typists and calculators attacking other people on sight. People who would have been farm hands, typists, calculators or shirt makers in an earlier generation are working in other fields today.

One thing is changing, though, and that is education. When people mostly worked farms, most had little or no education at all. Twelve years of education, to say nothing of a stay at university, was an unimaginable (literally) luxury for the few and the male in the wealthy upper classes. Factory workers and others did need basic schooling to do their jobs, and some years in school became the norm; a full twelve years was for the well to do, and university a rare privilege. Later nine years or so became compulsory, and twelve years - high school or so - became the norm for employability. Today having just high school is the bare minimum for societal participation, and a short college/university education is common. I'd expect that two-year or three-year college will be the minimum education level another generation or two from now, and I certainly expect this trend to continue further still.

But this is not the problem it may seem. An education level once seen as appropriate only for the upper class movers and shakers of the world - and certainly too demanding for fragile female minds - is today a level that any construction worker, Macdonalds fry cook or TV personality sees as a completely natural level to have attained and surpassed (well, attained at least, for TV personalities). A university degree, once a rare thing, a mark of distinction and an automatic portal to high status is today something rather common, if not banal, attainable by the likes of me.

But this is not the problem it may seem. An education level once seen as appropriate only for the upper class movers and shakers of the world - and certainly too demanding for fragile female minds - is today a level that any construction worker, Macdonalds fry cook or TV personality sees as a completely natural level to have attained and surpassed (well, attained at least, for TV personalities). A university degree, once a rare thing, a mark of distinction and an automatic portal to high status is today something rather common, if not banal, attainable by the likes of me.

The point is, we tend to be capable of much more than our own expectations allow. Female heads did not in fact overheat and explode once subjected to rigorous education; instead women are surpassing men in all intellectual disciplines. The "lower classes" and their educationability that was the cause of such worry a century or two ago turn out to be exactly as proficient as upper-class kids if given the same opportunities. More to the point, when 10-12 years of education is the norm, you get the same success rate as you did when 3-4 years was the standard. Kids seen as failing today still manage more - much more - than a level considered successful a century and a half ago. Expectations and opportunity govern our educational outcome more than ability does. Check back in in another fifty years and you'll have people anxious about the students that never manage to finish two-year college.

It does mean that our adolescence will continue to lengthen. Once you were an adult once your voice broke; today you're not effectively an adult until 20 or even older. Once three years of college is the minimum, you'll be adolescent at least until 25. As life expectancy also rises there will be a shift in working life, starting later and retiring later than now. Sure, 25 will be the new 18 and 50 may be the new 40 - the age of menopause is rising - but expect 75 to be the new 65 as well.

Monday, December 15, 2008

Recipe: Homemade Soba noodles

The New Year is coming up, and one tradition is to eat soba noodles. Soba is a common kind of noodle in Japan, along with udon and ramen. They're thin, dull grey noodles made of buckwheat with a rustic appearance. The flavour is a bit nutty and gritty, unlike udon which, being made of wheat, is similar to pasta.

You eat soba either hot in a bowl, perhaps with deep-fried vegetables or other toppings; or cold, dipped in a cup of salty sauce and slurped. Soba was first made only with buckwheat so they fell apart very easily (buckwheat doesn't have gluten). Because of that they were steamed rather than boiled, and often served right out of the bamboo steam tray, called "zaru". Nowadays the buckwheat is mixed with some wheat and boiled, but cold soba - "zarusoba" - is still traditionally served on a bamboo tray.

Last winter we made homemade soba. I was completely convinced that I posted a blog entry about this at the time, but as it turns out I never did (or I just can't find it). Better late than never.

When you eat it at home you normally just buy a pack of dried or fresh soba. But it's fun to try to make things yourself, and if you're not living in Japan dried soba can be difficult to find, so it's well worth taking a shot at making it by hand. The original soba used only buckwheat (there's still restaurants serving that). Today you usually use a mix of two parts wheat to eight parts buckwheat; the wheat gluten helps hold the noodles together and lightens the taste a bit. Below I'll be using equal parts buckwheat and wheat, a common mix, and easier to work with.

The ingredients: Buckwheat flour, wheat flour, potato starch (actually "katakuriko", dogtooth starch, but potato starch works the same) and water. We'll need a rolling pin and a bowl too. I used equal parts buckwheat and wheat; for a bit more authentic noodle you should use 8:2 but that's a bit harder to work. Water is about half the flour by weight.

First, mix the buckwheat and wheat flour together. Make a dent in the center of the flour mix and pour in some water. Mix it well together; it should become a fairly dry ball of dough. A rule of thumb is that the dough should feel like pinching an earlobe.

Work the dough very well, by repeated folding and stretching. Here is where I made a major mistake: I worked the dough only for about five-ten minutes, like I do when baking bread. You should work it longer. Shape the dough into a smooth ball with no air pockets.

The reason you work dough is for the gluten in the flour to attach to itself and start forming long protein chains, and those chains are what holds the whole thing together. But with a dough that is only part wheat the gluten proteins has a harder time finding copies to attach to. Also, a wet, loose dough lets the molecules slip around and move about quite easily but in a dry dough like this it is much more difficult for them to move around and attach to each other.

A wheat-only dough or a really wet dough does not need to be worked much. But a dough like this needs to be worked a lot, much more than the few minutes I gave it. There is in fact a long sequence of steps for working soba dough, and if you follow those steps you will have worked the dough enough at the end.

Roll out the dough with the rolling pin, using the katakuriko (or potato flour) to avoid it sticking. First make a large round sheet, then you make it square by repeatedly rolling up the dough on the rolling pin, roll it out, then repeat at a 90 degree angle. Sprinkle katakuriko (or potato starch) to avoid sticking. However you do, you should have a square or rectangular sheet in the end.

Fold the sheet into thirds, with plenty of katakuriko to avoid any sticking. Put the dough on a cutting board.

Use the largest knife you have to gently cut the dough into thin, thin strips. This is not that easy. Ideally you should have a special sliding board on top to guide you and a huge, cleaver-like soba-knife to cut the noodles. Just using a large, sharp kitchen knife works though.

Fluff up the noodles a bit to make them separate properly and get rid of excess starch. Boil up water, then boil the soba for 1.5 minutes or so. Immediately dunk them in cold water to stop them cooking further. As I didn't work the soba enough previously, our noodles tended to fall apart as they cooked, giving us short, stumpy noodles rather than the long ones we're supposed to have.

You eat soba either hot in a bowl, perhaps with deep-fried vegetables or other toppings; or cold, dipped in a cup of salty sauce and slurped. Soba was first made only with buckwheat so they fell apart very easily (buckwheat doesn't have gluten). Because of that they were steamed rather than boiled, and often served right out of the bamboo steam tray, called "zaru". Nowadays the buckwheat is mixed with some wheat and boiled, but cold soba - "zarusoba" - is still traditionally served on a bamboo tray.

Last winter we made homemade soba. I was completely convinced that I posted a blog entry about this at the time, but as it turns out I never did (or I just can't find it). Better late than never.

When you eat it at home you normally just buy a pack of dried or fresh soba. But it's fun to try to make things yourself, and if you're not living in Japan dried soba can be difficult to find, so it's well worth taking a shot at making it by hand. The original soba used only buckwheat (there's still restaurants serving that). Today you usually use a mix of two parts wheat to eight parts buckwheat; the wheat gluten helps hold the noodles together and lightens the taste a bit. Below I'll be using equal parts buckwheat and wheat, a common mix, and easier to work with.

The ingredients: Buckwheat flour, wheat flour, potato starch (actually "katakuriko", dogtooth starch, but potato starch works the same) and water. We'll need a rolling pin and a bowl too. I used equal parts buckwheat and wheat; for a bit more authentic noodle you should use 8:2 but that's a bit harder to work. Water is about half the flour by weight.

First, mix the buckwheat and wheat flour together. Make a dent in the center of the flour mix and pour in some water. Mix it well together; it should become a fairly dry ball of dough. A rule of thumb is that the dough should feel like pinching an earlobe.

Work the dough very well, by repeated folding and stretching. Here is where I made a major mistake: I worked the dough only for about five-ten minutes, like I do when baking bread. You should work it longer. Shape the dough into a smooth ball with no air pockets.

The reason you work dough is for the gluten in the flour to attach to itself and start forming long protein chains, and those chains are what holds the whole thing together. But with a dough that is only part wheat the gluten proteins has a harder time finding copies to attach to. Also, a wet, loose dough lets the molecules slip around and move about quite easily but in a dry dough like this it is much more difficult for them to move around and attach to each other.

A wheat-only dough or a really wet dough does not need to be worked much. But a dough like this needs to be worked a lot, much more than the few minutes I gave it. There is in fact a long sequence of steps for working soba dough, and if you follow those steps you will have worked the dough enough at the end.

Roll out the dough with the rolling pin, using the katakuriko (or potato flour) to avoid it sticking. First make a large round sheet, then you make it square by repeatedly rolling up the dough on the rolling pin, roll it out, then repeat at a 90 degree angle. Sprinkle katakuriko (or potato starch) to avoid sticking. However you do, you should have a square or rectangular sheet in the end.

Fold the sheet into thirds, with plenty of katakuriko to avoid any sticking. Put the dough on a cutting board.

Use the largest knife you have to gently cut the dough into thin, thin strips. This is not that easy. Ideally you should have a special sliding board on top to guide you and a huge, cleaver-like soba-knife to cut the noodles. Just using a large, sharp kitchen knife works though.

Fluff up the noodles a bit to make them separate properly and get rid of excess starch. Boil up water, then boil the soba for 1.5 minutes or so. Immediately dunk them in cold water to stop them cooking further. As I didn't work the soba enough previously, our noodles tended to fall apart as they cooked, giving us short, stumpy noodles rather than the long ones we're supposed to have.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

The Devotion of Suspect X

Or, "容疑者Xの献身" in the original. The book, a murder mystery, is part of a series by Keigo Higashigo. It's fairly recent and due to be turned into a movie. Compared to Reason it is a significantly easier read, and the book is shorter as well, so it should be reasonably quick. On the other hand, as it is easier I have time to really make sure I do understand everything so it may not be that much faster overall. I started it on the 1st of December and have read the first chapter. I thought I'd summarize each chapter here as I finish them. If you intend to read the book and don't want to know the plot it may be a good idea to skip these posts in the future.

Chapter 1

Our tale starts with Tetsuya Ishigami, teacher in mathematics, on his way to work in a Tokyo school. He is sharp-eyed and friendly, as evidenced by his reflecitions on the people he meets during his walk. On the way, he stops by the Bentencho lunch-box takeout place. This is not strictly because he needs lunch, but because of his secret crush on the shop assistant..

..Yasuko Hanaoka, divorcee and former bar hostess. She left hostessing for a shop assistant job when her daughter Misato was getting old enough to start school. When shop owner Sayoko Yonezawa points out that the teacher guy seems to have a crush on her and knows which days she comes to work, Yasuko freaks out. She has no favourable impression of the middle-aged and chubby Ishigami and worries he may be stalking her. The reason for her distrust soon becomes clear as the shop gets a visit from her estranged former husband..

..Shinji Toshige, smooth-talking former car salesman; you can practically hear the oily hair and too-sharp suit in the text. He swept her off her feet when they first met at a bar; they married, had Misato and Yasuko quit working. But soon Toshige was fired for embezzlement and he settled on a life of drinking and gambling while Yasuko returns to bar hostessing to earn money, money which he promptly takes from her. Tired of the abuse she finally files for divorce, but he continues to stalk her and her daughter and demanding money until she quits her job and moves away to start over at the lunch-box restaurant. I don't think we're supposed to like this guy very much.

He insists that they get together again for unstated reasons and he threatens to catch Misato at her school if Yasuko doesn't agree to meet him after work. He sneers, he even laughs evilly. She meets him after work and refuses his advances. Once she gets home, however, it turns out he's followed her. He forces himself in, smokes against her wish, makes a general nuisance of himself, and pockets some of her money almost absentmindedly. Really, all the guy needs is a goatee and a cape and the character is complete.

As Misato comes home he is naturally a complete bastard towards her as well. As she flees into another room, he follows her briefly then returns and starts to leave. As he bends to put on his shoes Misato shows up - and swings a heavy copper vase at the back of his head, felling him like an ox. Is he hurt? Is he dead? Is he going to be not happy at all about this? Ah, but that will be made clear in the next chapter...

Chapter 1

Our tale starts with Tetsuya Ishigami, teacher in mathematics, on his way to work in a Tokyo school. He is sharp-eyed and friendly, as evidenced by his reflecitions on the people he meets during his walk. On the way, he stops by the Bentencho lunch-box takeout place. This is not strictly because he needs lunch, but because of his secret crush on the shop assistant..

..Yasuko Hanaoka, divorcee and former bar hostess. She left hostessing for a shop assistant job when her daughter Misato was getting old enough to start school. When shop owner Sayoko Yonezawa points out that the teacher guy seems to have a crush on her and knows which days she comes to work, Yasuko freaks out. She has no favourable impression of the middle-aged and chubby Ishigami and worries he may be stalking her. The reason for her distrust soon becomes clear as the shop gets a visit from her estranged former husband..

..Shinji Toshige, smooth-talking former car salesman; you can practically hear the oily hair and too-sharp suit in the text. He swept her off her feet when they first met at a bar; they married, had Misato and Yasuko quit working. But soon Toshige was fired for embezzlement and he settled on a life of drinking and gambling while Yasuko returns to bar hostessing to earn money, money which he promptly takes from her. Tired of the abuse she finally files for divorce, but he continues to stalk her and her daughter and demanding money until she quits her job and moves away to start over at the lunch-box restaurant. I don't think we're supposed to like this guy very much.

He insists that they get together again for unstated reasons and he threatens to catch Misato at her school if Yasuko doesn't agree to meet him after work. He sneers, he even laughs evilly. She meets him after work and refuses his advances. Once she gets home, however, it turns out he's followed her. He forces himself in, smokes against her wish, makes a general nuisance of himself, and pockets some of her money almost absentmindedly. Really, all the guy needs is a goatee and a cape and the character is complete.

As Misato comes home he is naturally a complete bastard towards her as well. As she flees into another room, he follows her briefly then returns and starts to leave. As he bends to put on his shoes Misato shows up - and swings a heavy copper vase at the back of his head, felling him like an ox. Is he hurt? Is he dead? Is he going to be not happy at all about this? Ah, but that will be made clear in the next chapter...

Monday, December 8, 2008

JLPT 1

Yes, it's this time of year again, when Japanese learners of all levels leave their solitary dens to gather and mingle like lemmings, if lemmings were to mingle in unheated university lecture halls on an early Sunday morning in December. And today, after one years absence, I gathered with all the rest.

As I accidentally passed level 2 two years ago, my next - and last - level is level 1. I plan to try to take it next year, and so I took level 1 now just to have a base of comparison. That means I did no studying or preparation whatsoever for this year, not even looking at an earlier test; I want to see what I know and what I don't. So of course I'll flunk this one. That's OK; it's on purpose.

This is not an easy event to photograph. Worn classrooms aren't intrinsically photogenic, and I think it'd be impolite and perhaps even a breach of privacy to post an easily recognizable image of a test-taker. Oh well.

First of all, kanji and vocabulary. It is a lot more difficult than level 2 was and I didn't stand a chance. This is the most criticized part of the level 1 test as the questions frequently go beyond just testing your knowledge and into the realm of word puzzles. You may be asked to match words using the same kanji given only their pronunciation, for instance. Ugh. Some practice is called for here. So far my kanji studies have been piecemeal and ad hoc; it seems I'll need a more structured approach the coming year.

The listening part went so-so; not very difficult as such, but I did miss a fair few questions due to my deficient vocabulary. I didn't expect to have to work a lot on my listening and it looks like I won't have to.

Reading was the positive surprise of the day. I managed to pass level 2 mainly on the strength of this section and again I did a lot better than I thought I would. Spending every weekday morning the past couple of years with my nose in a book has been paying off I guess. Again my limited vocabulary tripped me up a lot, but I even though I thought I was too slow in reading everything I still managed to have almost 40 minutes left for the grammar section. Again, I won't need any specific reading practice for next year.

The grammar... I've never enjoyed studying grammar, and I've only just started covering the frequently obscure or rare grammar that comes up at this level. I actually knew a couple of the grammar questions, could make informed guesses on some but basically just answered most of them completely at random. I really need to get to work on this.

The maximum score is 400, and the passing score is 280. If you just guess on everything you can expect around 100 points. Me, I should have somewhere around 150-180 points or so I think. Which is fine - the lower my current score, the more I'll have improved when I retake it next year after all.

As I accidentally passed level 2 two years ago, my next - and last - level is level 1. I plan to try to take it next year, and so I took level 1 now just to have a base of comparison. That means I did no studying or preparation whatsoever for this year, not even looking at an earlier test; I want to see what I know and what I don't. So of course I'll flunk this one. That's OK; it's on purpose.

This is not an easy event to photograph. Worn classrooms aren't intrinsically photogenic, and I think it'd be impolite and perhaps even a breach of privacy to post an easily recognizable image of a test-taker. Oh well.

First of all, kanji and vocabulary. It is a lot more difficult than level 2 was and I didn't stand a chance. This is the most criticized part of the level 1 test as the questions frequently go beyond just testing your knowledge and into the realm of word puzzles. You may be asked to match words using the same kanji given only their pronunciation, for instance. Ugh. Some practice is called for here. So far my kanji studies have been piecemeal and ad hoc; it seems I'll need a more structured approach the coming year.

The listening part went so-so; not very difficult as such, but I did miss a fair few questions due to my deficient vocabulary. I didn't expect to have to work a lot on my listening and it looks like I won't have to.

Reading was the positive surprise of the day. I managed to pass level 2 mainly on the strength of this section and again I did a lot better than I thought I would. Spending every weekday morning the past couple of years with my nose in a book has been paying off I guess. Again my limited vocabulary tripped me up a lot, but I even though I thought I was too slow in reading everything I still managed to have almost 40 minutes left for the grammar section. Again, I won't need any specific reading practice for next year.

The grammar... I've never enjoyed studying grammar, and I've only just started covering the frequently obscure or rare grammar that comes up at this level. I actually knew a couple of the grammar questions, could make informed guesses on some but basically just answered most of them completely at random. I really need to get to work on this.

The maximum score is 400, and the passing score is 280. If you just guess on everything you can expect around 100 points. Me, I should have somewhere around 150-180 points or so I think. Which is fine - the lower my current score, the more I'll have improved when I retake it next year after all.

Friday, December 5, 2008

H.M. Has Passed Away

In the news today, H.M. has passed away. "H.M.", well known by anyone who has ever studied brain science or neuroscience, are the initials for a patient who had radical surgery in 1953 in order to stop his debilitating epilepsy seizures. The surgery involved removing both Hippocampus and Amygdala on both sides.

This did indeed stop the seizures, but it also gave him profound anterogade amnesia - he could no longer form new memories. He could remember most things up until a few days before his surgery, but could not form any new long-term memories after this point. Think about it: every morning he woke up believing it was still 1953 and he was still 27. Doctors and nurses that had seen him for years had to introduce themselves to him if they left his side for a few hours.

He became one of the most studied people in modern medicine, and his tragic case taught us an enormous amount about how memory actually works. Generations of brain researchers know about him and the research his case has spawned. It is through him, for instance, that we know that semantic, or episodic memory - remembering events, for instance - is different and distinct from short-term memory and procedural memory. You can learn to do something without ever remembering having learned it.

At one time a researcher brought H.M. a Tower of Hanoi puzzle. H.M. cheerfully admitted to never having heard of the puzzle in his life. He worked on the puzzle until he somehow managed to solve it, after which the researcher left, taking the puzzle with him. The next day the researcher returned. For H.M. this was all new again: he had never heard of the puzzle (or the researcher) in his life. He worked on the puzzle until he solved it, and the researcher left.

This went on for some days. And every day, H.M. would manage to solve the puzzle faster and better until he clearly had "got" the way you solve it. But while he clearly had learned the optimal solution to the puzzle - procedural memory - he still had no recollection of ever having heard of the puzzle. Procedural memory and declarative memory are different systems in the brain.

In 2002 Nature Neuroscience published a review article (PDF) that summarizes half a century of research with H.M. and his life during that period. It's well worth reading.

Henry G. Molaison, now no longer anonymous, passed away at age 82. In accordance with his wishes, a detailed autopsy will be performed on his brain.

This did indeed stop the seizures, but it also gave him profound anterogade amnesia - he could no longer form new memories. He could remember most things up until a few days before his surgery, but could not form any new long-term memories after this point. Think about it: every morning he woke up believing it was still 1953 and he was still 27. Doctors and nurses that had seen him for years had to introduce themselves to him if they left his side for a few hours.

He became one of the most studied people in modern medicine, and his tragic case taught us an enormous amount about how memory actually works. Generations of brain researchers know about him and the research his case has spawned. It is through him, for instance, that we know that semantic, or episodic memory - remembering events, for instance - is different and distinct from short-term memory and procedural memory. You can learn to do something without ever remembering having learned it.

At one time a researcher brought H.M. a Tower of Hanoi puzzle. H.M. cheerfully admitted to never having heard of the puzzle in his life. He worked on the puzzle until he somehow managed to solve it, after which the researcher left, taking the puzzle with him. The next day the researcher returned. For H.M. this was all new again: he had never heard of the puzzle (or the researcher) in his life. He worked on the puzzle until he solved it, and the researcher left.

This went on for some days. And every day, H.M. would manage to solve the puzzle faster and better until he clearly had "got" the way you solve it. But while he clearly had learned the optimal solution to the puzzle - procedural memory - he still had no recollection of ever having heard of the puzzle. Procedural memory and declarative memory are different systems in the brain.

In 2002 Nature Neuroscience published a review article (PDF) that summarizes half a century of research with H.M. and his life during that period. It's well worth reading.

Henry G. Molaison, now no longer anonymous, passed away at age 82. In accordance with his wishes, a detailed autopsy will be performed on his brain.

Wednesday, December 3, 2008

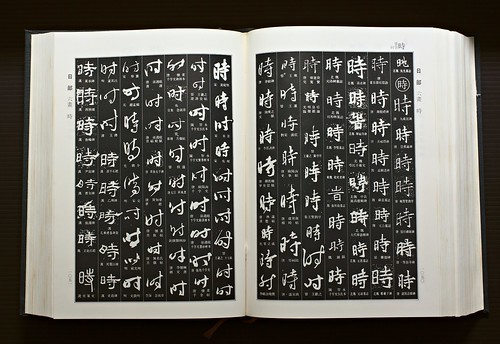

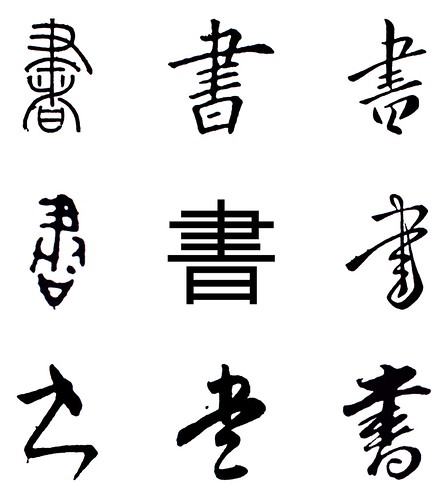

Hanko Typography

The owner of Neat & Grog here in Osaka sometimes holds barbecues at his parents place. His father is a former hanko maker. A hanko is the namestamp you use here instead of a signature. It's usually the kanji comprising your family name laid out in a circle or, sometimes, oval or square. In my case I have no kanji of course so my hanko spells out my family name in katakana instead. They can be simple, like mine, or very large and complex, as in the case of official hanko for businesses or public authorities. People will usually have more than one stamp, with one official hanko, and one or more casual stamps. The official one is registered to your name at the local ward office; you'd use that one only for important business like buying a house or car, or dealing with your bank. Then you have one or more casual stamps you use for signing post packages, receipts and so on.

Hanko are sometimes criticized as being inherently unsafe, since it is possible, if somewhat tedious, to copy the exact image. But then, a signature is just as insecure - if not more so, as a persons signature varies quite a lot, making it even more difficult to determine if it's the "same" signature. But that is beside the point. The real value of signatures and hanko lies not in the markings on a piece of paper but in the act of applying the mark. You have a standard gesture where you show that you accept or approve whatever the document is stating. Making that gesture, especially when witnessed by third parties, is what confers validity. The resulting mark is secondary.

Anyway, as a hanko maker he has a lot of books related to the business, and one I found intensely fascinating was a collection of hanko from different makers, grouped by character. It gives a focused view of just how large a variety of graphical forms can still be considered the same in some abstract sense. Those of us who have grown up using the roman alphabet are quite used to seeing wildly varying letter-forms and think nothing of it, even when they're so obscure as to be unreadable out of context. The enormous variety hits you more when you see to see it in graphical forms you're not familiar with to the same intimate degree.

Hanko are sometimes criticized as being inherently unsafe, since it is possible, if somewhat tedious, to copy the exact image. But then, a signature is just as insecure - if not more so, as a persons signature varies quite a lot, making it even more difficult to determine if it's the "same" signature. But that is beside the point. The real value of signatures and hanko lies not in the markings on a piece of paper but in the act of applying the mark. You have a standard gesture where you show that you accept or approve whatever the document is stating. Making that gesture, especially when witnessed by third parties, is what confers validity. The resulting mark is secondary.

Anyway, as a hanko maker he has a lot of books related to the business, and one I found intensely fascinating was a collection of hanko from different makers, grouped by character. It gives a focused view of just how large a variety of graphical forms can still be considered the same in some abstract sense. Those of us who have grown up using the roman alphabet are quite used to seeing wildly varying letter-forms and think nothing of it, even when they're so obscure as to be unreadable out of context. The enormous variety hits you more when you see to see it in graphical forms you're not familiar with to the same intimate degree.

Monday, December 1, 2008

Minolta SRT 101

The Minolta SRT101 is one of the classic cameras of the 1970's. It was introduced in 1966 and was in production for fifteen years - an eternity by today's standards. It was hugely popular, in part because of its light-metering system, but also because it is an extremely solid, reliable camera with a large array of high-quality lenses available. This is not a "vintage camera"; it is quite capable of excellent results used today, and apart from autofocus there is nothing this camera lacks compared to its modern counterparts. Except for it being a film camera, of course; I'll come to that.

This is notable for being one of the first mainstream cameras with "open aperture metering". It meant that unlike earlier SLR cameras, the lens aperture setting is coupled to the body, so the camera knows which aperture you would be using. The light meter measures the light with the lens wide open, then compensates for the aperture you'll actually use. Very convenient, and perhaps obvious today, but it was a real innovation at the time.

This camera has several other real benefits such as a dedicated mirror lock-up knob. When you take a picture, the mirror inside slams up so the light can reach the shutter instead of the viewfinder, but that jolts the camera and creates blur at lower shutter speeds. To avoid that, especially on a tripod, you want to fold up the mirror beforehand. Many modern DSLR cameras unfortunately hide this useful function in some obscure menu (Pentax, to their credit, have a really smart function for this). This camera has a very convenient dedicated lever for it. And when something is convenient you tend to use it, which results in better images.

But the most notable feature of this camera is the body itself. It's squared-off, all metal, and built to last. To make it short, it feels like a steel ingot in your hands. This is good and bad. Good thing is, it can probably take quite a lot of abuse with only superficial wear and tear. On the downside, it really is quite heavy; it certainly feels heavier than my K10D despite being a lot smaller. It's dangerous in a way; it feels so solid and reliable you tend to forget to be careful. And solid or not, if you bang it hard enough the small mechanical assemblies inside are not going to like it very much. In reality, of course, modern camera design with a rigid metal cage surrounded by a plastic shell is lighter, cheaper and just as durable, if not more so.

But the most notable feature of this camera is the body itself. It's squared-off, all metal, and built to last. To make it short, it feels like a steel ingot in your hands. This is good and bad. Good thing is, it can probably take quite a lot of abuse with only superficial wear and tear. On the downside, it really is quite heavy; it certainly feels heavier than my K10D despite being a lot smaller. It's dangerous in a way; it feels so solid and reliable you tend to forget to be careful. And solid or not, if you bang it hard enough the small mechanical assemblies inside are not going to like it very much. In reality, of course, modern camera design with a rigid metal cage surrounded by a plastic shell is lighter, cheaper and just as durable, if not more so.

But while the time of all-metal bodies have gone, the shape is a different matter: A square slab with well-defined edges feels much better in your hands than the rather bulbous, swollen camera bodies of today. A modern DSLR feels like a large balloon-animal toy version of the Minolta. They look like they have the mumps. I really, really wished camera makers could return to this kind of sleek, well defined body shape.

As far as taking pictures with the Minolta, things are remarkably simple. Look through the viewfinder, adjust aperture and shutter speed until a little paddle thingy matches the light meter needle, focus and shoot. Film has a remarkable latitude so this simple light meter is plenty accurate enough, and as the camera has an old-style coarse ground glass it's very easy to see when you're in focus (unlike today's brighter but smaller viewfinders).

Our basil plant just before we cut it down to make pesto; and the escalators in Crysta Nagahori leading up to the street level. White balance used to be an issue with film, but when you process the images digitally you can tweak it as much as you want.

And About That Film Issue?

The last issue is that of film. I've already mentioned that I've started to use film in addition to digital. But that is medium-format film, and black and white rather than color. the thing is, the larger the film area the easier it is to get good results, and the easier it is to scan. We may think of 35mm - and APS format digital SLRs - as a consumer format, if we even realize that other formats exist. But because the film or sensor area is relatively small it needs higher quality lenses and higher precision than medium format to achieve good results.

Medium and large-format lenses are usually less sharp and resolve less detail than 35mm lenses, and - counterintuitively for a "professional" format - they are cheaper as a result. Sure, there are medium format lenses that approach the resolution of a good 35mm lens but they're relatively rare and expensive. With all that sensor area medium format lenses don't need to be very sharp; instead some sharpness is sacrificed in exchange for lower noise and higher dynamic range.

The same scene shot with 35mm film (left) and digital SLR (right). Somewhat different colors, and a somewhat more muted rendering with the film version than the digital one. I think I prefer the film version in this case.

As far as resolution there's no meaningful difference I can see when comparing the negative with the digital file. In reality, neither film nor digital camera sensors are constrained by resolution any more; it's other factors like lens aberrations and resolution, diffraction and so on that are the limits today.

This same principle holds at the other end too. Medium format negatives are really large and forgiving so even a mediocre scanner will still get a high resolution, decent quality scan out of it. But with the small frame size of a 35mm negative you need a better scanner for decent results. We have two scanners at home - an old but good quality flatbed that Ritsuko uses for work and I scan medium format with, and our HP all-in-one printer, copier and scanner which also has the ability to scan 35mm film.

The good quality flatbed does a decent job, with low noise and OK color rendering, though white balance needs to be adjusted afterwards. Flatbed scanners normally achieve only half their theoretical optical resolution or even less, however, so at a practical limit of 1200 dpi this one gives rather small images for 35mm. The all-in-one is a fine document scanner and copier but for film it gives results so bad that I won't even show them here; they're completely useless, with lots of shadow noise with some strange random shot noise, blocked highlights, striping and wonky color rendering (not just a white balance problem, but wrong altogether). Lesson: for scanners the low end really can be worse than nothing.

In the End

I'll keep using this camera, I think. It's a stellar camera and the 50/1.7 normal on it does it justice. For all its bulk it is still smaller than my MF cameras, and it should be fun to keep it in the bag as an always-around camera. Not sure if I'll keep using color film or if I go with BW here too, and start developing 35mm myself as well. Time will tell. The whole set of images is available here.

Thursday, November 27, 2008

No Reason

I've finally finished "Reason" by Miyuki Miyabe, after just about a year of reading, mostly on the morning train. To recap, the story begins with a multiple murder in a Tokyo high rise; four people are dead - three stabbed inside the apartment, one jumped or pushed from the balcony. It turns out they are not related to each other in any way even though they lived together as a family.

Miyabe explores the reasons for the murder by looking at the lives and backgrounds of all the people involved with or touched by the events. It is written in a documentary style where the author interviews people about a year after the crime, trying to piece together the events leading up to the murder. We often get to hear about the same event or situation from different viewpoints; sometimes the recollections differ so much they could be different events altogether. Some characters are appealing and likable, others are truly disagreeable. But Miyabe treats them all evenhandedly and with a surprising amount of sympathy and understanding.

「理由」 means "reason" or "motive" but also "pretext". The title alludes to unearthing the reasons for the murder, but the actual murder is really only discussed in the first part of the book, and then again at the very end. The crime is just a pretext for Miyabe to delve into the lives of a disparate group of characters that would otherwise have little in common. And I really mean delve; even staffage characters that would otherwise come and go within a single paragraph can still get a page or two with their life story, their concerns and their worries. It seems clear to me that Miyabe is really writing about the lives of all these ordinary people, and the crime story is there mostly to give her a reason to do so.

So, how was it?

The book is difficult. Really difficult; in fact, my teacher first recommended it to me but soon had second thoughts. She realized that it was too difficult for my level, but decided not to discourage me by telling me so. At first I could barely manage two or three sentences over one commute, and even now towards the end I manage perhaps five or six pages on a good day. One reason is that we have a lot of people in the book, more than a dozen central characters and perhaps twice as many again in supporting roles. All of them have their own way of speaking, often using Tokyo dialect, schoolyard slang or rough spoken language. In one chapter a lawyer was using legal language and terminology to such an extent I basically gave up on understanding it all and just focused on getting the gist of his explanation. When a plot follows just a few central characters you get used to the way they speak, but here we keep shifting from person to person, never staying long enough to really get comfortable.

The second source of difficulty is her use of unusual or archaic writing. A Japanese word can often be written either in hiragana or kanji, and sometimes with a choice of kanji. Problem is, Miyabe has never met an unusual kanji she didn't like. Some words are normally written using hiragana, such as "ある", to exist; but Miyabe prefers to use the unusual kanji form "在る" whenever she can. The word "listen" is normally written as "聞く" but Miyabe prefers to use "訊く" instead, with the same meaning but rare enough that my Japanese-English dictionary doesn't even have it. ALC has 774 example sentences using "聞く", and 1 (one) using "訊く". A few unusual forms like this is OK, but she uses them a lot, and that slows down my reading something fierce. It's like linguistic flypaper, trapping the freeflowing tale in a sticky mess of obscure language.

With that said, the book is good. It is, in fact, excellent. I spent a year slowly reading through the slow story, endless digressions and asides, and getting caught in the language traps she litters throughout the text - and yet I never once thought about quitting, that's how good it is. She is simply a very engaging storyteller, and can relate something seemingly banal, like the business difficulties of a sandwich shop, in a way that makes it interesting, even engrossing. The most ordinary lives cease to be ordinary once they get depicted with skill and flair. If you can read Japanese (and better than me, preferably) you could do much worse than to pick this one up.

What's next? Don't know yet. I'll wait a bit before I decide what to tackle next. Another mystery or crime novel would be good, though a little easier and faster to read. I'll see what my teacher will recommend; this one was an excellent choice so I have no doubt her next suggestion will be good too.

Miyabe explores the reasons for the murder by looking at the lives and backgrounds of all the people involved with or touched by the events. It is written in a documentary style where the author interviews people about a year after the crime, trying to piece together the events leading up to the murder. We often get to hear about the same event or situation from different viewpoints; sometimes the recollections differ so much they could be different events altogether. Some characters are appealing and likable, others are truly disagreeable. But Miyabe treats them all evenhandedly and with a surprising amount of sympathy and understanding.

「理由」 means "reason" or "motive" but also "pretext". The title alludes to unearthing the reasons for the murder, but the actual murder is really only discussed in the first part of the book, and then again at the very end. The crime is just a pretext for Miyabe to delve into the lives of a disparate group of characters that would otherwise have little in common. And I really mean delve; even staffage characters that would otherwise come and go within a single paragraph can still get a page or two with their life story, their concerns and their worries. It seems clear to me that Miyabe is really writing about the lives of all these ordinary people, and the crime story is there mostly to give her a reason to do so.

So, how was it?

The book is difficult. Really difficult; in fact, my teacher first recommended it to me but soon had second thoughts. She realized that it was too difficult for my level, but decided not to discourage me by telling me so. At first I could barely manage two or three sentences over one commute, and even now towards the end I manage perhaps five or six pages on a good day. One reason is that we have a lot of people in the book, more than a dozen central characters and perhaps twice as many again in supporting roles. All of them have their own way of speaking, often using Tokyo dialect, schoolyard slang or rough spoken language. In one chapter a lawyer was using legal language and terminology to such an extent I basically gave up on understanding it all and just focused on getting the gist of his explanation. When a plot follows just a few central characters you get used to the way they speak, but here we keep shifting from person to person, never staying long enough to really get comfortable.

The second source of difficulty is her use of unusual or archaic writing. A Japanese word can often be written either in hiragana or kanji, and sometimes with a choice of kanji. Problem is, Miyabe has never met an unusual kanji she didn't like. Some words are normally written using hiragana, such as "ある", to exist; but Miyabe prefers to use the unusual kanji form "在る" whenever she can. The word "listen" is normally written as "聞く" but Miyabe prefers to use "訊く" instead, with the same meaning but rare enough that my Japanese-English dictionary doesn't even have it. ALC has 774 example sentences using "聞く", and 1 (one) using "訊く". A few unusual forms like this is OK, but she uses them a lot, and that slows down my reading something fierce. It's like linguistic flypaper, trapping the freeflowing tale in a sticky mess of obscure language.

With that said, the book is good. It is, in fact, excellent. I spent a year slowly reading through the slow story, endless digressions and asides, and getting caught in the language traps she litters throughout the text - and yet I never once thought about quitting, that's how good it is. She is simply a very engaging storyteller, and can relate something seemingly banal, like the business difficulties of a sandwich shop, in a way that makes it interesting, even engrossing. The most ordinary lives cease to be ordinary once they get depicted with skill and flair. If you can read Japanese (and better than me, preferably) you could do much worse than to pick this one up.

What's next? Don't know yet. I'll wait a bit before I decide what to tackle next. Another mystery or crime novel would be good, though a little easier and faster to read. I'll see what my teacher will recommend; this one was an excellent choice so I have no doubt her next suggestion will be good too.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

IKEA

Ikea is: A source of inexpensive design furniture; a famously penny-pinching but attractive employer; killer of local furniture stores; a symbol of globalized trade gone wild. For Swedish exiles like me, Ikea is a so-so restaurant and seller of hard to find Swedish foods that just happens to also sell furniture in the back.

Ikea is really popular here; during rush hours you still sometimes have to stand in line outside the store to get in. Better to go during off-hours with less people, no lines to the restaurant and more time to browse.

The warehouse area feels like the soul of Ikea. This is where the magic happens; where the shimmering dream from the showroom upstairs comes true, manifested in oblong boxes with mystical incantations like "Granemo", "Ektorp" and "Numerär" offered in supplication to appease the Dark Gods of Furniture Assembly Resting Eternally (Though Very Comfortably) Outside Space And Time1.

Last year we got an Ikea store in Kobe, out on Port Island in the bay. It's right next to a train station and the trip from home takes us an hour or so; we often go to Kobe anyway so it's not far. This August, another store finally opened in Osaka. It's out in the Taishō harbour district to the southwest, not that far from where we live. This is great - or, it would have been had the location been slightly different.

Ikea likes harbours and industrial parks. The land is cheap, it's easy to reach with a car or delivery truck, and such areas are often economically depressed so they can get tax breaks and development help from the local governments. But the Osaka store out by the bay is far from any train or subway station. You can take the subway halfway to the store, then line up for an Ikea shuttle bus running every twenty minutes; or you can go to Namba, then stand in line for the shuttle bus running from there. Either way it takes almost exactly as long for us to go to Ikea in Osaka as to Ikea in Kobe - and when we go to Kobe we don't need to stand in line for a bus.

On the other hand, the Osaka Ikea is right in the harbour area - a real, working industrial harbour - and the human male isn't born that doesn't find freight ships, cranes, and the whole dilapidated industrial environment fascinating, even romantic. It is, I think, a mix of the big, bulky hands-on technology on display, with the promise of faraway travel and adventure; it's a glimpse of life beyond the ordinary. Just going to the harbour area is a treat, whether or not you actually stop by a furniture store on the way.

The last time we went to Ikea in Osaka, therefore, we didn't go by bus but on bicycle. It is about 8 km if you go more or less straight there. Not that far, especially since much of Osaka is flat and bicycle-friendly. On the other hand, "straight there" is pretty much impossible for me, so it took a while.

There's several large, high bridges in the harbour, and amazingly most of them have walkways and bicycle lanes on them. There's no better place to get a good birds-eye view of the area. Just don't be too worried about heights.

There's lots of places like this in the area. Small side canals with rundown piers, forgotten old boats and equipment. Sure, they're dirty, dingy and decaying. Yes, they're marks of poverty and failure. No, none of these places will ever be finalists in the Urban Sparkling Radiant Freshness Award of the Year competition. But they have a hesitant beauty of their own, I think, one worth preserving or at least acknowledge before they disappear.

---

#1If you happen to own a Theremin, this is the time to take it out for some quick sound effects.

Ikea is really popular here; during rush hours you still sometimes have to stand in line outside the store to get in. Better to go during off-hours with less people, no lines to the restaurant and more time to browse.

The warehouse area feels like the soul of Ikea. This is where the magic happens; where the shimmering dream from the showroom upstairs comes true, manifested in oblong boxes with mystical incantations like "Granemo", "Ektorp" and "Numerär" offered in supplication to appease the Dark Gods of Furniture Assembly Resting Eternally (Though Very Comfortably) Outside Space And Time1.

Last year we got an Ikea store in Kobe, out on Port Island in the bay. It's right next to a train station and the trip from home takes us an hour or so; we often go to Kobe anyway so it's not far. This August, another store finally opened in Osaka. It's out in the Taishō harbour district to the southwest, not that far from where we live. This is great - or, it would have been had the location been slightly different.

Ikea likes harbours and industrial parks. The land is cheap, it's easy to reach with a car or delivery truck, and such areas are often economically depressed so they can get tax breaks and development help from the local governments. But the Osaka store out by the bay is far from any train or subway station. You can take the subway halfway to the store, then line up for an Ikea shuttle bus running every twenty minutes; or you can go to Namba, then stand in line for the shuttle bus running from there. Either way it takes almost exactly as long for us to go to Ikea in Osaka as to Ikea in Kobe - and when we go to Kobe we don't need to stand in line for a bus.

On the other hand, the Osaka Ikea is right in the harbour area - a real, working industrial harbour - and the human male isn't born that doesn't find freight ships, cranes, and the whole dilapidated industrial environment fascinating, even romantic. It is, I think, a mix of the big, bulky hands-on technology on display, with the promise of faraway travel and adventure; it's a glimpse of life beyond the ordinary. Just going to the harbour area is a treat, whether or not you actually stop by a furniture store on the way.

The last time we went to Ikea in Osaka, therefore, we didn't go by bus but on bicycle. It is about 8 km if you go more or less straight there. Not that far, especially since much of Osaka is flat and bicycle-friendly. On the other hand, "straight there" is pretty much impossible for me, so it took a while.

There's several large, high bridges in the harbour, and amazingly most of them have walkways and bicycle lanes on them. There's no better place to get a good birds-eye view of the area. Just don't be too worried about heights.

There's lots of places like this in the area. Small side canals with rundown piers, forgotten old boats and equipment. Sure, they're dirty, dingy and decaying. Yes, they're marks of poverty and failure. No, none of these places will ever be finalists in the Urban Sparkling Radiant Freshness Award of the Year competition. But they have a hesitant beauty of their own, I think, one worth preserving or at least acknowledge before they disappear.

---

#1If you happen to own a Theremin, this is the time to take it out for some quick sound effects.

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Press Photo

We had an accident just two blocks away from here recently, at a small restaurant. A group had eaten nabe - stew cooked at the table on a small gas burner. When the table was cleared away some less than blindingly bright waiter put the gas burner on an unused kitchen gas stove. A cook turned on the stove by mistake, and found out why small gas canisters carry big warnings about never ever putting them in a fire. Nobody died in the resulting explosion, but four people had to be taken to the hospital.

Since nobody knew the causee, or whether there'd be further explosions, the fire brigade and police came out in force, with lots of loud trucks and cars, and cordoned off a good part of the street. And of course journalists, press photographers and TV crews congregated like moths to a fire. We passed by on our evening walk a little later and stopped to watch. I didn't care about the accident site - there was nothing much to see from far away, and unlike the journalists I have no business with other people's misfortune - but the assembled photographers were interesting. I figured I could always learn something new about photography from seeing how they worked. And I did - apparently the first rule of photojournalism is "always bring your stepladder".

The first thing that hit me was, everybody had a stepladder. Everybody. People discuss cameras, lenses, tripods, strobes and so on, but nobody brings up the humble aluminum stepladder as a crucial piece of photographic equipment. It makes sense, of course. If you're a press photographer you tend to cover visually striking events, and such events will bring a crowd that you'll need to get above or ahead of in order to get a decent picture.

Now, this is either pure force of habit or something like a good-luck charm, but I fail to see any conceivable advantage of the stepladder here. Maybe he just feels naked without it. Maybe he has an irrational fear of naked mole rats and wants a bit of safety distance to the ground while he's otherwise occupied. I didn't ask.

The accident happened at night and on a quiet back street, and the initial drama was already over when we came by, so there weren't that many people about anymore. Still, there was plenty enough photographers still milling around. And as we can see, a stepladder is useful as a laptop table too, when you need to review your shots.

Since nobody knew the causee, or whether there'd be further explosions, the fire brigade and police came out in force, with lots of loud trucks and cars, and cordoned off a good part of the street. And of course journalists, press photographers and TV crews congregated like moths to a fire. We passed by on our evening walk a little later and stopped to watch. I didn't care about the accident site - there was nothing much to see from far away, and unlike the journalists I have no business with other people's misfortune - but the assembled photographers were interesting. I figured I could always learn something new about photography from seeing how they worked. And I did - apparently the first rule of photojournalism is "always bring your stepladder".

The first thing that hit me was, everybody had a stepladder. Everybody. People discuss cameras, lenses, tripods, strobes and so on, but nobody brings up the humble aluminum stepladder as a crucial piece of photographic equipment. It makes sense, of course. If you're a press photographer you tend to cover visually striking events, and such events will bring a crowd that you'll need to get above or ahead of in order to get a decent picture.

Now, this is either pure force of habit or something like a good-luck charm, but I fail to see any conceivable advantage of the stepladder here. Maybe he just feels naked without it. Maybe he has an irrational fear of naked mole rats and wants a bit of safety distance to the ground while he's otherwise occupied. I didn't ask.

The accident happened at night and on a quiet back street, and the initial drama was already over when we came by, so there weren't that many people about anymore. Still, there was plenty enough photographers still milling around. And as we can see, a stepladder is useful as a laptop table too, when you need to review your shots.

Monday, November 17, 2008

Kanazawa

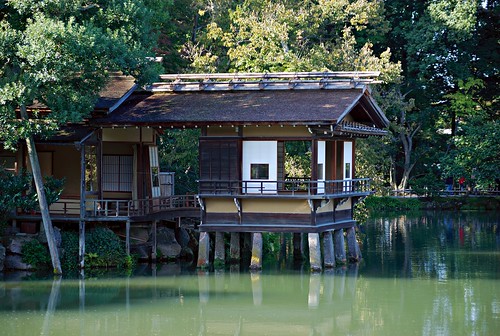

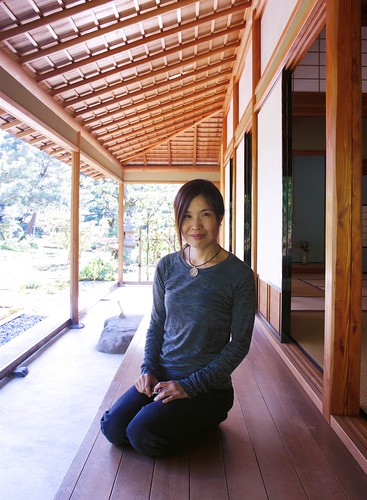

In our slowly evolving grand tour of the Japanese islands we took a day trip to Kanazawa a couple of weeks ago. It's a medium-sized city on the Japanese Sea side, due north from Kansai. The train from Osaka takes about 2.5 hours, making it just reachable without spending too much time traveling. An acquaintance of Ritsuko's was having an art exhibition at the city museum giving us a reason to go.

The place is said to be famous for its seafood - but then, Japan is an island nation and obsessive about food; every place here is famous for its seafood, in its own eyes if nothing else. In fact, if there's a place in Japan not famous for its seafood - perhaps even known for its lack of quality and variety - I think I would like to visit it. So would, I guess, plenty of other people. Places become travel destinations when they offer something different after all, and whatever could be more different here than not having good seafood?

The place is said to be famous for its seafood - but then, Japan is an island nation and obsessive about food; every place here is famous for its seafood, in its own eyes if nothing else. In fact, if there's a place in Japan not famous for its seafood - perhaps even known for its lack of quality and variety - I think I would like to visit it. So would, I guess, plenty of other people. Places become travel destinations when they offer something different after all, and whatever could be more different here than not having good seafood?

It could have a big market with excellent meat, poultry, and eggs, stalls heaped high with vegetables, cheeses, locally made miso and tofu - any and all kind of land-based food you could imagine. In one corner would be a single tourism board-employed fishmonger offering a small, sorry selection of seafood. Perhaps a few sad-looking bony river fish and a single pack of Norwegian smoked salmon well past its sell-by date. You'd have people flocking five deep around the poor man, taking his picture, buying up local produce for presents back home and fighting for phone straps and postcards featuring the local logo. Perhaps a cute, cartoonish dead-smelly-fish character would be appropriate?

Anyway, Kanazawa. It's a decent-sized city of 450.000 people, larger than Aomori (which we visited recently) by almost half, and with a decently busy atmosphere. Plenty of tourists on the street too. There's the art museum I mentioned above; some restored old entertainment neighbourhoods; the remains of the castle; a large, bustling fish market; and, most famous, the Kenroku garden, one of the three foremost gardens in Japan.

We came off the train (scenic ride, by the way) and walked from the station, via the fish market towards the museum. The whole city is quite compact so walking around is no problem. We stopped by for something to eat before going to the museum; culture is best experienced on a full stomach.

Restaurant Ōtsuka is an inexpensive eatery on a back street in central Kanazawa. It's a place of buckling linoleum floors and dark brown wood interior getting darker and browner from many years of tobacco smoke and stains. Tin plates, scratched glassware and beer crates in the corner. If you're looking for luxury, look elsewhere.

But if you're looking for a homey atmosphere, wonderful food, shelves of manga to read and generally a place to put up your feet and relax for a while then this is the place to go. Were I to live in Kanazawa I would happily grow old(er) and fat(ter) in this place.

Hanton rice is a local specialty and a specialty at the Ōtsuka restaurant. Like the nationally popular dish of omuraisu (from "omelet and rice"), it's a heaping of tomato sauce-flavoured rice wrapped in a creamy omelet. But hanton rice adds fried seafood - fish and shrimp - to the omelet and tops it with big dollops of ketchup and mayonnaise. This is some seriously heavy food, true, and probably a health disaster but it is absolutely, amazingly delicious. I wish there was a place in Osaka that served this.

After lunch we walked over to the museum. It is startlingly like just about any recent art museum anywhere in the world. A low-slung structure with white, angular surfaces, and a sprinkling of permanent artworks comissioned for the site. As I believe I wrote in the Aomori post, I consider this a good thing. You come there for the exhibitions and not the building, and anything that elevates the artwork over the architecture is good. As always there's no good pictures of the actual exhibition we came for and any photography in the exhibition halls was forbidden.

They do a good job at this museum of keeping visitors - younger visitors especially - interested with their permantent installations. This pool was really cool, and very popular too.

I'm a little ambivalent towards this kind of piece though. It's basically having one fun or offbeat idea and taking it as far as it goes. I love that kind of stuff, and many a technology or science demonstration is conceived and realized in the same way. I'm just not sure it qualifies as art. This pool doesn't seem to have any meaning or message to the viewer other than "Hey, look, cool isn't it?" This would fit in a trade-show booth (ok, a big booth) or world expo pavilion as much as an art museum. Not that I'm complaining.

The Kenroku gardens is the main reason most people come to this city. It's considered one of the three top public gardens in the country. It is very beautiful, with sculpted greenery, carefully planned views and dotted with teahouses and other small buildings. It is also overrun with visitors. Out of the way corners and the less spectacular views are easy enough to get to, but the main points of interest were frankly so crowded we gave up on trying to get a good look.

Every autumn workers attach ropes to the wide-branched trees in the park like this so that the heavy, wet snow of winter doesn't break them. No safety harnesses needed for this job, apparently.

You can find solitude and stillness in the park - if you are patient and if only for the 1/40 of a second you need for a picture.

This stone lantern is famous, and stands as a symbol of the city. It is apparently also all but impossible to photograph this time of day without catching half a dozen other people. Popular spot.

After the gardens we walked across the river to Higashi Chayamachi ("Eastern Tea house street"), an old Geisha entertainment street, preserved more or less intact. Nice, though again full of people. There's some teahouses, restaurants and the inevitable accessory and sweet shops; Japanese tourists are more commonly women rather than men and tourist spots plan accordingly.

By the time we passed by the fish market again - to pick up some crab we'd bought - it was getting dark already. We had dinner at a sushi place in the market, then walked across the street to a department store with a very relaxing cafe with a good city view on the eight floor.