From Slate, an interesting take on the automation of manufacturing. While people in the US (and Japan) worry a lot about the outsourcing of the manufacturing base and the resulting loss of jobs, a surprising amount of work today is automated, not outsourced.

Automation has a long history and it's easy to lose sight of just how much it has changed the workplace over the years. Early in the industrial era nuts and bolts were actually made one by one, turned by a skilled machinist, and matched to each other so you'd have parts that fit. As late as mid last century companies maintained typing pools where skilled women neatly typed out documents based on handwritten notes. Not that long ago "Calculator" was still a job title, rather than a counting machine.

Automation has a long history and it's easy to lose sight of just how much it has changed the workplace over the years. Early in the industrial era nuts and bolts were actually made one by one, turned by a skilled machinist, and matched to each other so you'd have parts that fit. As late as mid last century companies maintained typing pools where skilled women neatly typed out documents based on handwritten notes. Not that long ago "Calculator" was still a job title, rather than a counting machine.

We have been losing work - production and service jobs alike - to machines for centuries already. This has periodically flared up as a hot-button issue, last time in the 1980's when there was a lot of fear that industrial robots and computers would cause permanent mass unemployment. Suddenly, though, the issue seemed to vanish. Industrial robots of the era were large, expensive and complex and unsuitable in most factory settings, and office automation created lots of new jobs and business opportunities that soaked up people even as old office professions disappeared. When opening markets and improved communications created an outsourcing boom in the 1990's, any thoughts of machines competing with humans were forgotten.

Outsourcing - specifically, outsourcing to emerging countries like China, India, Vietnam, eastern Europe and so on - is not a new phenomenon either. For well-to-do families in northern Europe a set of china (sic) with the family monogram and illustrations, commissioned and imported from China, was the very thing to have in the 1700's. The recent boom is probably noteworthy mostly because this time the driver is cost and because of the large number of industries involved more than anything else.

This trend to outsource is not permanent. It is arbitraging the wage differences between industrialized and emerging markets, but over time those differences are lessening and mostly remove any simple cost-related reasons to outsource production. This is overall a good thing; a huge amount of people in emerging markets are pulling theselves out of poverty. While the wage differential may have been the prime driver this time around, other reasons to outsource to other countries are as valid as ever so some outsourcing will persist no matter what. Some people hope that as costs rise - from wage level increases, transportation costs or import duties - that production will return to the industrialized countries. The production may well return, but the jobs, by and large, will not.

Outsourcing is really only a side show - a dress rehersal if you will. Many tasks today are done manually not because we can't automate them, but simply because a machine that can do it is still more expensive than a human, and especially a poorly paid human in a third-world sweatshop. The spread of automation did not stop, as the article shows, it just slowed when it had to compete with some very low production costs in the emerging world. But robotics and information technology continues to become cheaper and more capable even as salary levels increase. A shirt that once was sewn in France or England is now being sewn in Vietnam or Bangladesh, but will at some point in the future be made by a sewing robot. And where that robot is located will no longer really matter as far as sewing, cutting and trimming jobs are concerned.

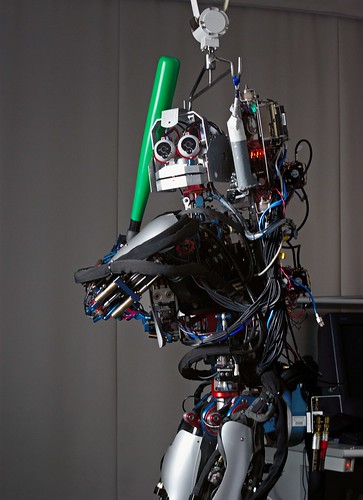

The range of professions being touched by automation is increasing. Far from big, dumb metal arms doing repetitive welding or painting, industrial robots are very capable machines already, and the possibility exists for far more autonomous, resourceful systems that can handle very complicated tasks without supervision or detailed instructions. Again, to a fair degree it is already a matter of cost rather than ability. Imagine a sewing robot that can take shirt design CAD files - perhaps measured for a particular customer - a pile of cloth and by itself sort out the materials, cut the cloth, sew the panels, and add all trimming. The next week it'll do jeans. The next week in turn a special order for a boat sail, and all without any explicit programming or expensive reconfiguration. If there's too much work, just add another unit on the factory floor. If business is slow, just idle a few of them - or rent them to another producer - until things pick up again.

The rise of very capable dataprocessing and communication is changing service jobs in the same way. In Sweden, economic information about your wage, loans, real estate ownership, capital transactions and so forth is submitted by employers and banks, and is complete enough that for most people the tax office can prefill and precalculate most of your taxes automatically, including deductions and benefits. The tax code is as complex as ever, but whereas we all had to manually figure it out one by one, the tax office now has enough computing power and know-how to easily encode the very complex rules and regulations and apply them for the inhabitants of the entire country over the span of a few weeks, and improvements in communications technology and standards mean the tax office now has the data needed to do those calculations directly. This capability really is new, and it really is significant. After all, much of the complexity and anxiety of doing your taxes was to figure out which rule to apply when and how to go about it. That complexity is now automated.

The remaining job of checking the data and adding any additional info is now very easy - easy enough that most people need no help or further instruction at all. Very convenient, a big money and time saver for people and the tax office alike, and a major yearly stress moment gone for a lot of people. But it also destroyed the whole individual market for accountants and tax lawyers, how-to books and tax preparation software. Sure, a few people still need or want tax assistance but it's become a purely high-end boutique service, not a mass market. Automation has removed a class of service jobs, in other words, and not a low-end kind of work either.

So, disaster for humanity then? No. As I've written above, this is a very old trend, and we have seen this played out several times before. Once upon a time, the vast majority of people where more or less directly involved in agriculture and fishery while today only a small percentage are, even as production improvements mean the yield is much higher than ever before. But that never gave rise to 80% unemployment, as changes were slow and people adapted. Our streets are notably empty of roving gangs of feral typists and calculators attacking other people on sight. People who would have been farm hands, typists, calculators or shirt makers in an earlier generation are working in other fields today.

One thing is changing, though, and that is education. When people mostly worked farms, most had little or no education at all. Twelve years of education, to say nothing of a stay at university, was an unimaginable (literally) luxury for the few and the male in the wealthy upper classes. Factory workers and others did need basic schooling to do their jobs, and some years in school became the norm; a full twelve years was for the well to do, and university a rare privilege. Later nine years or so became compulsory, and twelve years - high school or so - became the norm for employability. Today having just high school is the bare minimum for societal participation, and a short college/university education is common. I'd expect that two-year or three-year college will be the minimum education level another generation or two from now, and I certainly expect this trend to continue further still.

But this is not the problem it may seem. An education level once seen as appropriate only for the upper class movers and shakers of the world - and certainly too demanding for fragile female minds - is today a level that any construction worker, Macdonalds fry cook or TV personality sees as a completely natural level to have attained and surpassed (well, attained at least, for TV personalities). A university degree, once a rare thing, a mark of distinction and an automatic portal to high status is today something rather common, if not banal, attainable by the likes of me.

But this is not the problem it may seem. An education level once seen as appropriate only for the upper class movers and shakers of the world - and certainly too demanding for fragile female minds - is today a level that any construction worker, Macdonalds fry cook or TV personality sees as a completely natural level to have attained and surpassed (well, attained at least, for TV personalities). A university degree, once a rare thing, a mark of distinction and an automatic portal to high status is today something rather common, if not banal, attainable by the likes of me.

The point is, we tend to be capable of much more than our own expectations allow. Female heads did not in fact overheat and explode once subjected to rigorous education; instead women are surpassing men in all intellectual disciplines. The "lower classes" and their educationability that was the cause of such worry a century or two ago turn out to be exactly as proficient as upper-class kids if given the same opportunities. More to the point, when 10-12 years of education is the norm, you get the same success rate as you did when 3-4 years was the standard. Kids seen as failing today still manage more - much more - than a level considered successful a century and a half ago. Expectations and opportunity govern our educational outcome more than ability does. Check back in in another fifty years and you'll have people anxious about the students that never manage to finish two-year college.

It does mean that our adolescence will continue to lengthen. Once you were an adult once your voice broke; today you're not effectively an adult until 20 or even older. Once three years of college is the minimum, you'll be adolescent at least until 25. As life expectancy also rises there will be a shift in working life, starting later and retiring later than now. Sure, 25 will be the new 18 and 50 may be the new 40 - the age of menopause is rising - but expect 75 to be the new 65 as well.

With these fast-paced times, more and more things might have been automated by now, but that doesn't change the fact that human intervention is still needed at certain intervals.

ReplyDeleteHuman intervention is still occasionally needed even in the most automated of fields. But as far as mass employment is concerned it is of no consequence.

ReplyDeleteIt won't matter if factory employment, for instance, decreases by 90%, 95% or 99%; in any case its role as an employment driver is well and truly over. The same goes for any other field.