Friday, December 31, 2010

Saturday, December 25, 2010

White Christmas

I understand that Sweden has a spot of weather at the moment. Not to be outdone, as we left home earlier this morning we saw actual snowflakes - plural! - wafting down from the sky.

I guess this technically counts as a white Christmas for Osaka - you know, in the same way that Ozawa may be technically innocent of graft. But for weather as for election laws it's technical that counts.

Friday, December 24, 2010

Merry Christmas

It's Christmas Eve, and I'm taking a break from my end-of year panic together with Ritsuko. We've had a non-traditional cross-cultural Christmas dinner (meaning fried chicken, apple salad, cake, cheese and wine) and I'm mellowing out with the last of the wine while writing this post.

To the left is Akasaka Prince Hotel in Tokyo. It's a distinctive building in a pretty well-done 1970's style, and they apparently do some large-scale decorations for Christmas every year. This is the last Christmas though; it's slated to close and get torn down next year. Just to the right, beyond the edge of the picture, is restaurant Stockholm, where we had Swedish Smörgåsbord last week.

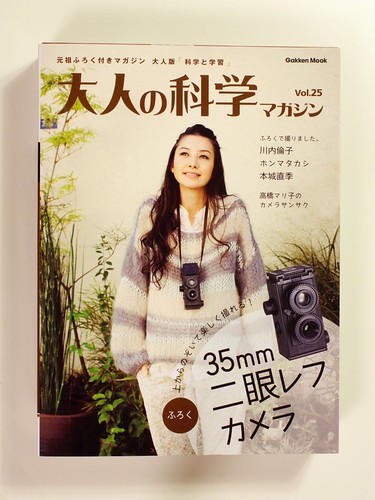

Oh, and we've had presents too, of course. Here's mine:

To the left is Akasaka Prince Hotel in Tokyo. It's a distinctive building in a pretty well-done 1970's style, and they apparently do some large-scale decorations for Christmas every year. This is the last Christmas though; it's slated to close and get torn down next year. Just to the right, beyond the edge of the picture, is restaurant Stockholm, where we had Swedish Smörgåsbord last week.

Oh, and we've had presents too, of course. Here's mine:

Otona No Kagaku is a great series of sciency kits for adults, with a new issue every few months. I've been eyeing this twin-lens camera kit ever since it was released early this year, and now Ritsuko gave it to me for Christmas. She knows me only too well I think.

Merry Christmas everyone!

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Quickie Time - Bic Camera Edition

It's a national holiday today - which for me mostly means I get to work from home. But I did go out over lunch, and popped in to Bic Camera in Namba.

First, they have the Sony E-reader I mentioned in my previous post. I brought a memory card with a couple of research papers in PDF format to try out. Surprisingly, it works quite well. I first tried playing with the zoom function but that was too cumbersome. Then I noticed it has several modes for PDF reading, and one mode divides each page in four, showing you one quarter at a time. That works perfectly for typical two-column PDFs. Clear and easy to read, and all illustrations and all math came out perfect as well. Perhaps I should see if I can buy one for the project next year...

Second, Bic in Namba has not been very good for film camera users the past year or two, with a small, unreliable selection of films and developing gear. I'm happy to say this has changed. They now have most black and white films I know about, including a complete selection of Ilford films and even Ilfords Kentmere brand films and some Czech Foma films (tip: Fomapan 400 is best used at iso 200).

Third, I asked about medium format film developing at Bic, and to my surprise they do both medium format negative and slide film development in an hour, the same as for 35mm. Most places - including Naniwa and Yodobashi in Umeda - take a couple of days to do it. Very convenient, and worth remembering.

First, they have the Sony E-reader I mentioned in my previous post. I brought a memory card with a couple of research papers in PDF format to try out. Surprisingly, it works quite well. I first tried playing with the zoom function but that was too cumbersome. Then I noticed it has several modes for PDF reading, and one mode divides each page in four, showing you one quarter at a time. That works perfectly for typical two-column PDFs. Clear and easy to read, and all illustrations and all math came out perfect as well. Perhaps I should see if I can buy one for the project next year...

Second, Bic in Namba has not been very good for film camera users the past year or two, with a small, unreliable selection of films and developing gear. I'm happy to say this has changed. They now have most black and white films I know about, including a complete selection of Ilford films and even Ilfords Kentmere brand films and some Czech Foma films (tip: Fomapan 400 is best used at iso 200).

Third, I asked about medium format film developing at Bic, and to my surprise they do both medium format negative and slide film development in an hour, the same as for 35mm. Most places - including Naniwa and Yodobashi in Umeda - take a couple of days to do it. Very convenient, and worth remembering.

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Back Home

We've just arrived home from our Tokyo weekend. I'll write a picture-post thing later, when I'm done with the images. Until then, a few random observations:

* I didn't have real internet access all weekend, and it was wonderful. Well, I did have my smartphone of course, but it doesn't invite you to random surfing for hours on end. I'm bone tired, but I feel way more relaxed than I ever do after a normal weekend.

* We passed a Sony store and I took a quick look at their new e-book reader, the Touch 650. It was, well ... amazing, really. I mean, I almost bought it right there and then, and had Ritsuko - always a voice of reason - not been along I really would have plonked down the money right in the store.

It's an e-ink based reader, like the Kindle from Amazon. Which means it really looks like paper rather than a screen. It's nicely bright and contrasty (black and white photographs look pretty good), and there's a typical "flash" when you change pages. So far, so good.

But it's light. Really light; the weight feels like a thin pocket book, and you could easily hold it for hours on end without getting tired. Could have it in a pocket or in your bag and never know it's there. And it has a touch-screen, so you can navigate by swiping your finger, you can click on icons and type notes right on screen. It even has a simple drawing program that is surprisingly useful; the e-ink screen only has to update a small bit at a time so it doesn't lag. Surprisingly (for Sony), it supports plenty of open formats, so it's easy to get texts on it. No net connection but USB and SD cards are supported. The battery is good for weeks.

I've tried the Kindle 3 too - it has the same screen - and the Sony is just plain better. It's lighter, smaller and the touch screen makes using it much more natural. For reading it handily beats tablets like the Samsung Tab and the iPad; they're heavier (much heavier for the iPad) and don't have the battery life or the paper-like screen.

Why didn't I get it then (apart from Ritsuko reminding me I don't actually need it)? Research papers. A major reason for me to get it would be to read research papers in PDF format. They are notoriously difficult to read well on-screen; I usually resort to printing them. An e-ink screen should render them much better. But I suspect the screen size (15cm - 6 inches) and the PDF reader application just aren't up to the task of showing them properly. I didn't have any example PDF-files with me, and I'm not going to buy a reader until I can test this properly.

* Most places in Japan sell a range of local specialities as travel gifts. "白い恋人" (shiroi koibito) is an extremely popular soft white chocolate cookie from Hokkaido. The name means "white sweetheart" and alludes to the white chocolate and to the wintery climate of the area. Coming back to Osaka tonight we spotted a gift store at the station selling a cookie called "面白い恋人" (omoshiroi koibito). Which means, roughly, "interesting sweetheart" or "amusing sweetheart". That, to me, sums up Osaka pretty well. I'm happy to be back.

* I didn't have real internet access all weekend, and it was wonderful. Well, I did have my smartphone of course, but it doesn't invite you to random surfing for hours on end. I'm bone tired, but I feel way more relaxed than I ever do after a normal weekend.

* We passed a Sony store and I took a quick look at their new e-book reader, the Touch 650. It was, well ... amazing, really. I mean, I almost bought it right there and then, and had Ritsuko - always a voice of reason - not been along I really would have plonked down the money right in the store.

It's an e-ink based reader, like the Kindle from Amazon. Which means it really looks like paper rather than a screen. It's nicely bright and contrasty (black and white photographs look pretty good), and there's a typical "flash" when you change pages. So far, so good.

But it's light. Really light; the weight feels like a thin pocket book, and you could easily hold it for hours on end without getting tired. Could have it in a pocket or in your bag and never know it's there. And it has a touch-screen, so you can navigate by swiping your finger, you can click on icons and type notes right on screen. It even has a simple drawing program that is surprisingly useful; the e-ink screen only has to update a small bit at a time so it doesn't lag. Surprisingly (for Sony), it supports plenty of open formats, so it's easy to get texts on it. No net connection but USB and SD cards are supported. The battery is good for weeks.

I've tried the Kindle 3 too - it has the same screen - and the Sony is just plain better. It's lighter, smaller and the touch screen makes using it much more natural. For reading it handily beats tablets like the Samsung Tab and the iPad; they're heavier (much heavier for the iPad) and don't have the battery life or the paper-like screen.

Why didn't I get it then (apart from Ritsuko reminding me I don't actually need it)? Research papers. A major reason for me to get it would be to read research papers in PDF format. They are notoriously difficult to read well on-screen; I usually resort to printing them. An e-ink screen should render them much better. But I suspect the screen size (15cm - 6 inches) and the PDF reader application just aren't up to the task of showing them properly. I didn't have any example PDF-files with me, and I'm not going to buy a reader until I can test this properly.

* Most places in Japan sell a range of local specialities as travel gifts. "白い恋人" (shiroi koibito) is an extremely popular soft white chocolate cookie from Hokkaido. The name means "white sweetheart" and alludes to the white chocolate and to the wintery climate of the area. Coming back to Osaka tonight we spotted a gift store at the station selling a cookie called "面白い恋人" (omoshiroi koibito). Which means, roughly, "interesting sweetheart" or "amusing sweetheart". That, to me, sums up Osaka pretty well. I'm happy to be back.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

That Was Fast

Remember that I'd reached 77kg about a month ago? I've lost another kilo since then, without even trying. There's nothing like pervasive stress and lack of sleep to make you lose weight, I guess. Not that I lack appetite, mind you - I'm plenty hungry at dinner time - but I feel full as soon as I start eating.

Anyway, this is just a temporary problem. Tomorrow is my second vacation day of the year. Ritsuko is going to Tokyo even as I write, and after work tonight I will take the train and join her for a long weekend in the capital. We'll go see a big outdoor temple market in Asakusa, spend an afternoon in Jimbocho (home to hundreds of specialist used book sellers), have Smörgåsbord at a Swedish restaurant and probably spend Sunday in nearby Yokohama and its large, lively Chinatown.

I strongly suspect I'll gain back the weight I've lost, and then some, by the time we come back.

Anyway, this is just a temporary problem. Tomorrow is my second vacation day of the year. Ritsuko is going to Tokyo even as I write, and after work tonight I will take the train and join her for a long weekend in the capital. We'll go see a big outdoor temple market in Asakusa, spend an afternoon in Jimbocho (home to hundreds of specialist used book sellers), have Smörgåsbord at a Swedish restaurant and probably spend Sunday in nearby Yokohama and its large, lively Chinatown.

I strongly suspect I'll gain back the weight I've lost, and then some, by the time we come back.

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Writers Block - The Definitive Study

Writers block is all too common for anybody who writes. Fortunately, science is here to help. I just stumbled on a wonderful, brief classic paper on the failure of self-treatment of writers block, published in "Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis" in 1974, and freely accessible here. Go on - it's an easy read for non-specialists.

Of course, a lot of psychological research used to be focused exclusively on northern Europeans and Americans. We know better today than to generalize results from one culture to others, so a group of researchers have replicated the original study from a cross-cultural perspective here.

I really have to find a way to cite either study in my next paper.

Of course, a lot of psychological research used to be focused exclusively on northern Europeans and Americans. We know better today than to generalize results from one culture to others, so a group of researchers have replicated the original study from a cross-cultural perspective here.

I really have to find a way to cite either study in my next paper.

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

We Have a Communications Problem

We all recently got a nice example of how communication can go wrong, and how the research community suffers as a result.

A few weeks ago, NASA sent out a cryptic press release about an upcoming research finding "that will impact the search for evidence of extraterrestrial life." The net explodes with speculation, some wildly unfounded, some informed and down-to-earth.

The big day arrives, and it turns out to be an entirely terrestrial bit of research: Researchers have taken a type of arsenic-tolerant bacteria that lives in an arsenic-rich lake, and coaxed them to actually incorporate the arsenic into their own body chemistry. Kind of cool, but nothing extraterrestrial, no "new life" or some different kind of life or anything. The first round of news articles did their best to play it up as a major breakthrough, while the first reaction from actual researchers was cautious and not overly enthusiastic.

Good thing they were cautious. People have now studied the paper in more detail and the results don't look nearly as good as the authors first claimed. The results are tenuous and not well supported, and the bacteria may in fact not have incorporated arsenic as a functional part of their body chemistry at all.

So, we go from immense hype and speculation, to uncritical reporting of a less-exciting result, to serious doubt that there is any positive result to report on at all. Enormous excitement to complete letdown in a few weeks. What went wrong?

First, take a look at who finally popped the whole media balloon: working researchers in the field that read and reflected on the paper, then wrote up their comments on their blogs or on news sites. Would it not have been good for everyone if they'd be able to chime in right from the start, rather than weeks after the media frenzy? Why weren't they? Why did the whole thing crash so spectacularly?

A few weeks ago, NASA sent out a cryptic press release about an upcoming research finding "that will impact the search for evidence of extraterrestrial life." The net explodes with speculation, some wildly unfounded, some informed and down-to-earth.

The big day arrives, and it turns out to be an entirely terrestrial bit of research: Researchers have taken a type of arsenic-tolerant bacteria that lives in an arsenic-rich lake, and coaxed them to actually incorporate the arsenic into their own body chemistry. Kind of cool, but nothing extraterrestrial, no "new life" or some different kind of life or anything. The first round of news articles did their best to play it up as a major breakthrough, while the first reaction from actual researchers was cautious and not overly enthusiastic.

Good thing they were cautious. People have now studied the paper in more detail and the results don't look nearly as good as the authors first claimed. The results are tenuous and not well supported, and the bacteria may in fact not have incorporated arsenic as a functional part of their body chemistry at all.

So, we go from immense hype and speculation, to uncritical reporting of a less-exciting result, to serious doubt that there is any positive result to report on at all. Enormous excitement to complete letdown in a few weeks. What went wrong?

First, take a look at who finally popped the whole media balloon: working researchers in the field that read and reflected on the paper, then wrote up their comments on their blogs or on news sites. Would it not have been good for everyone if they'd be able to chime in right from the start, rather than weeks after the media frenzy? Why weren't they? Why did the whole thing crash so spectacularly?

One reason is spelled "embargo". Many news outlets refuse to cover events like published research unless they can publish their articles right when it's announced. A research project may take five years, and writing and publishing the paper can take six months or a year, but if your newspaper has to wait for two days while their reporter reads the paper they refuse to mention it. Also, the impact of publication is greater for the journal if it's accompanied by a flurry of press coverage at the same time.

What high-profile research journals do is embargo interesting papers: They forbid anybody involved from speaking about the research until the publication date, and give some science journalists advance access to the paper and to the researchers. That gives them time to prepare their articles and lets them all publish at the same time, with higher public impact for everyone.

There's a few problems with that of course. Since nobody else knows about the research the journalist can't ask other researchers for a different perspective. The "journalist" is reduced to a PR-flack rewriting the press release1 in their own words. That gives us all those completely uncritical, overly positive science articles like the ones accompanying this arsenic paper.

And the people who really are well-placed to give a solid opinion on the paper - other researchers - didn't have advance access, and couldn't give their opinion right at publication. We had to wait a week for that, and by that time the damage - to the researchers, to NASA's reputation and to the science journalists - had already been done.

This was made worse in this case by a misleading and sensationalist press release by NASA well before publication. It was designed to fan the flames of media hype from the start, and it succeeded admirably. The people who could normally pour some cold water of reason on those flames could not, since the paper was embargoed and could offer no solid opinion on it.

But research is peer-reviewed; why weren't the problems caught well before publication in the first place? We can't know for sure of course, but people are speculating that the problems were caught by reviewers, but were overruled by the journal editors.

The highest-profile journals like Science and Nature are different from the normal journals most papers get published in. They aim for a wide audience and tend to go for the ground-breaking and surprising stuff - the kind of research that leads to prices and fame (they are called glamour journals for a reason).

Now, they normally publish very high-quality research, don't get me wrong, and having a paper in either of those can make a career. I'd give a body part to have a paper in either journal2. But the reality is that while the research is often very high quality, the actual papers are not. Their allowed page count is too low to give a lot of details or a good bibliography, and in the scramble to be first they can sometimes be rushed and badly edited. I rarely cite a paper in Science or Nature - it's usually better to look for a longer, more thorough paper from the same group published in a normal research journal.

Newsworthiness can trump thoroughness, and people speculate that this is what happened here. From what I understand (this is not my own field) the group would have needed to conduct another series of control experiments to rule out plausible error sources, and that would have added six months or another year to the publication time. The editors may well have felt it was more important to get it out now, rather than wait another year and get scooped by a different group and different journal.

So, here's the problems, in turn: A paper gets substandard peer review, or the journal overrides the review in the interest of speed; the paper gets embargoed - kept in the dark from anybody with the competence to evaluate it - leaving journalists to interpret the results themselves, with no input from specialists; a besieged and attention-starved research organization publishes a factually wrong, hype-inducing press release that triggers a frenzy of speculation and media attention.

The one thing that's not a problem in this mess is the paper itself. Wrong papers are published all the time; that's part of how science works. We don't have peer review to catch wrong papers. It's there to catch papers that are uninteresting, or just replicating earlier results, or that have methodological or experimental problems.

You usually don't know if a paper is wrong until later - years or decades later, sometimes - when pitted against other results and analysed by other research groups. Einsteins theory of general relativity took four years to the first tentative tests and more than fifty years to get definite confirmation. The idea of an ether was around for centuries before getting disproved, and nobody still has a clue if some version of the string theory is the right description of the subatomic universe, more than forty years after it first appeared.

Now, if we'd not had an embargo this would never have become such a big problem. The paper would be published, people chime in on the science and it would never have become such a media debacle. Most journalists would probably have refrained from covering it, once they'd realized the paper wasn't all that amazing, and quite possibly wrong. The only reason to embargo results is to fan media attention, and as we see this can backfire spectacularly. If a newspaper refuses to cover a result unless they can get advance, exclusive access then tough - don't cover it. Embargoes are a bad idea.

But if you must have an embargo, make sure that 1) Everybody respects it - no advance press releases; and 2) include a selection of other researchers, not just journalists, among the people getting advance access. That'd cut the damaging hype, and it would give journalists a better basis on which to write their articles, and perhaps to decide it's not worth covering after all.

--

#1 And the paper, theoretically, though you'd be surprised how many science journalists have no background in science and couldn't read a research paper if their life depended on it. Rewritten press releases is too often all that you get.

#2 Well... One that grows back.

Monday, December 6, 2010

JeyEllPeeTee

Oh yes, the season of the Japanese Language Proficiency test is upon us once again. Yesterday was the first time I took the new, redesigned test. I no longer fail 1-kyuu; I now fail N1 instead. Same level, different name.

And different test. It's still a multiple-choice exam, and the overall questions are quite similar but there the similarity ends. The old test had three parts: vocabulary and kanji; listening; and reading and grammar. The new test puts vocabulary, kanji, reading and grammar into one section, with listening as the other one.

The test is, I believe, a fair bit shorter than before. It now starts after lunch and takes only four hours including a half-hour break. The listening section is as long as before, and possibly a bit more difficult. The picture questions are gone, instead there's a fast section with single sentences followed by possible responses. It's really more a test of knowing your expressions and reading tone than of simple comprehension. There are a few longer, more involved passages that really tax your ability to remember who is saying what (I failed miserably; I just can't keep long passages straight in my head).

The reading is as long as before, or longer. There must have been a dozen texts of various lengths, with questions both on the overall meaning and of specific expressions. The texts seemed to be "real" writing, without much editing for the test; overall a little easier than the Asahi Shinbun articles I try to read in the mornings but not by much. The last question was a page from an application form for financial grants to foreign post-graduate students, and you had to figure out which of a set of candidates would be eligible to receive the money, and what a specific candidate had to do before they could apply. I really suck at administrativia like this in any language so I'm pretty sure I messed this one up as well.

What has become shorter is grammar and vocabulary, to some extent, and especially kanji. There were none of the puzzle-like questions of the older test ("Select the answer sentence that has an underlined compound kanji word with the same pronunciation as the underlined compound word in the question sentence"), and there were overall fewer simple knowledge questions. Of course, the reading and listening parts all make heavy demand on kanji, vocabulary and grammar so it's still tested a lot, just not as much in isolation.

Overall, I think the new test is much better balanced. The focus (at least at level N1) is properly on comprehension and use of real-life Japanese, with less focus on memorizing facts for their own sake. If there is anything still missing, it would be a test of actual language production. Many language tests do have an essay-writing section or a live interview, but that would probably increase the cost too much to be realistic.

For my test, I did feel I know this a bit better than last year, but the test also seems a bit harder. The scoring system has completely changed, though, so I really have no idea how well I'll do. I did fail, but I don't know how badly. Anyway, I think it's time for me to try it for real next time around. I'll get an exam practice book and start studying for the test once my workload drops a little, then try to pass the thing next December.

And different test. It's still a multiple-choice exam, and the overall questions are quite similar but there the similarity ends. The old test had three parts: vocabulary and kanji; listening; and reading and grammar. The new test puts vocabulary, kanji, reading and grammar into one section, with listening as the other one.

The test is, I believe, a fair bit shorter than before. It now starts after lunch and takes only four hours including a half-hour break. The listening section is as long as before, and possibly a bit more difficult. The picture questions are gone, instead there's a fast section with single sentences followed by possible responses. It's really more a test of knowing your expressions and reading tone than of simple comprehension. There are a few longer, more involved passages that really tax your ability to remember who is saying what (I failed miserably; I just can't keep long passages straight in my head).

The reading is as long as before, or longer. There must have been a dozen texts of various lengths, with questions both on the overall meaning and of specific expressions. The texts seemed to be "real" writing, without much editing for the test; overall a little easier than the Asahi Shinbun articles I try to read in the mornings but not by much. The last question was a page from an application form for financial grants to foreign post-graduate students, and you had to figure out which of a set of candidates would be eligible to receive the money, and what a specific candidate had to do before they could apply. I really suck at administrativia like this in any language so I'm pretty sure I messed this one up as well.

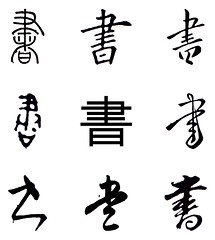

What has become shorter is grammar and vocabulary, to some extent, and especially kanji. There were none of the puzzle-like questions of the older test ("Select the answer sentence that has an underlined compound kanji word with the same pronunciation as the underlined compound word in the question sentence"), and there were overall fewer simple knowledge questions. Of course, the reading and listening parts all make heavy demand on kanji, vocabulary and grammar so it's still tested a lot, just not as much in isolation.

Overall, I think the new test is much better balanced. The focus (at least at level N1) is properly on comprehension and use of real-life Japanese, with less focus on memorizing facts for their own sake. If there is anything still missing, it would be a test of actual language production. Many language tests do have an essay-writing section or a live interview, but that would probably increase the cost too much to be realistic.

For my test, I did feel I know this a bit better than last year, but the test also seems a bit harder. The scoring system has completely changed, though, so I really have no idea how well I'll do. I did fail, but I don't know how badly. Anyway, I think it's time for me to try it for real next time around. I'll get an exam practice book and start studying for the test once my workload drops a little, then try to pass the thing next December.

Friday, December 3, 2010

New Kanji

This sort of slipped by this blog when it was first decided this spring, but Japan has increased the number of common-use kanji by almost two hundred, while removing half a dozen or so. The actual change is imminent, and prompted Asahi Shinbun to print an article on it last Wednesday, with a list of the new characters.

Common-use kanji (常用漢字) are the characters everybody learns in primary and high-school, as decided by the ministry of culture and education (and science, and technology and - for whatever reason - sports). There's around 2000 characters total - 2136 with this change - and an additional few hundred used for family and given names.

This list matters, as official documents and announcements, school materials and so on can use only characters on this list1. Private publishers can, and do, use whatever kanji they like of course, but it's generally a good idea to heed this list as your readers are guaranteed to know it.

Once upon a time the intention was to gradually abolish kanji. The common-use kanji list was a step in this direction, and newspapers and other publishers were required to stick to this list. But you can't dictate language use from above of course; just look at the futility of French governments trying to keep their language pure of Anglicisms for an example. Languages belong to its users, and it's the users that decide on use, not officials or language academies.

The education ministry no longer tries to dictate use; changes to this list are simply adapting to actual changes in real-world usage. The revision this time around is the largest increase in common-use kanji ever. The reason for the increase is of course that people are using more kanji than before (so much for abolishing them). And the reason for that, in turn, is the computer and the phone.

It's hard to remember how to write a character you rarely use. But it's much, much easier to recognize it when you see it. With a computer or phone you no longer need to remember exactly how to write them - you write the sound of each word and select the appropriate characters from a pop-up list. And there's a network effect: people start using rare characters in email and text, making them more common and encouraging other people to start using them too.

Is this automation bad? Nope. A decent analogy is English spelling: you no longer have to remember how to spellrodhorenron rhodorendron rhorhodenron rhonhorendron rhododendron; our spell checkers help us get it right. I wouldn't have tried to memorize that word - without a computer I would simply have written "dark green shrubbery plant", written it wrong or skipped it altogether.

Common-use kanji (常用漢字) are the characters everybody learns in primary and high-school, as decided by the ministry of culture and education (and science, and technology and - for whatever reason - sports). There's around 2000 characters total - 2136 with this change - and an additional few hundred used for family and given names.

This list matters, as official documents and announcements, school materials and so on can use only characters on this list1. Private publishers can, and do, use whatever kanji they like of course, but it's generally a good idea to heed this list as your readers are guaranteed to know it.

Once upon a time the intention was to gradually abolish kanji. The common-use kanji list was a step in this direction, and newspapers and other publishers were required to stick to this list. But you can't dictate language use from above of course; just look at the futility of French governments trying to keep their language pure of Anglicisms for an example. Languages belong to its users, and it's the users that decide on use, not officials or language academies.

The education ministry no longer tries to dictate use; changes to this list are simply adapting to actual changes in real-world usage. The revision this time around is the largest increase in common-use kanji ever. The reason for the increase is of course that people are using more kanji than before (so much for abolishing them). And the reason for that, in turn, is the computer and the phone.

It's hard to remember how to write a character you rarely use. But it's much, much easier to recognize it when you see it. With a computer or phone you no longer need to remember exactly how to write them - you write the sound of each word and select the appropriate characters from a pop-up list. And there's a network effect: people start using rare characters in email and text, making them more common and encouraging other people to start using them too.

Is this automation bad? Nope. A decent analogy is English spelling: you no longer have to remember how to spell

There are two kinds of additions: Kanji used in place names, and kanji already in common use in newspapers, advertisements and so on.

When I looked at the list itself I was surprised, frankly. Even I know a number of them, and I'd assumed many of them were common-use already. 嵐 (arashi - storm, tempest) for instance, or 潰 (tsubusu - to crush). 串 (kushi - skewer) and 貼 (haru - to stick) are both seen in streets everywhere as part of 串カツ (kushikatsu - Osaka-style meat skewers), and 貼り紙禁止 (harigami kinshi - "posters forbidden").

虎 (tora - tiger) and 熊 (kuma - bear) finally get their characters, though we may need to put them in a 籠 (kago - cage) and lock the 鍵 (kagi - key). We can now eat 鍋 (nabe - pot or stew) and 麺 (men - noodles) without resorting to hiragana. 狙 (nerau - aim), 袖 (sode - sleeve), 誰 (dare - who?) and 虹 (niji - rainbow) are other surprises.

Among place names we have 岡 (oka) as used in Fukuoka and Chizukoa, 奈 (na) for Nara and 阪 (saka) for Osaka.

Some other characters are still rare, overall, but show up in single words that are reasonably common. 鬱病 (utsubyou - depression) has become a poster-child for people opposed to this change; "utsu" is complicated and rare - even one of the components is very rare in itself - and really only used in this single word. Of course, people will mostly need to read it, not write it, and chances are this one will see more use too, once it becomes more familiar.

Overall, the change is a non-event for most people; they already know the characters, or will easily pick them up. Newspapers will adopt some of them and skip others for now. People will use them or not as they see fit. The real significance really is the fact of the increase in itself. It's a affirmation that kanji aren't going away, and an acknowledgement that technology has a role in driving language changes.

--

#1 You can use other characters if you add "furigana" - tiny kana characters indicating the pronunciation - to them. Book and magazine publishers sometimes use furigana for rare characters, and childrens and young adult books use them for any kanji the readers aren't expected to know yet. This is one reason that YA literature can be good practice material for adult language learners too.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)