A quick picture post: My evening commute as a collage of images, one per subway stop. I'm unsure if the idea really works; comments and advice is welcome.

Saturday, March 29, 2008

Thursday, March 27, 2008

Work Immigration

There's some interesting developments on work immigration in Sweden. The current government, together with the Green Party, is proposing that anybody, from anywhere, can automatically get a two year work permit if they have employment from a Swedish company. The requirements are that the job be properly advertised within the EU as well and that the job be full-time and come with the union-agreed salary, benefits, job security and all other conditions Swedish employees already get. The two year work permit would be extended another two years if they're still employed, and permanent work residency be granted if they're still employed after four years. Note that especially the benefit requirement - which the unions will be sure to enforce fiercely - really precludes the use of this as a way to dump salaries or import low-wage manual work; taking someone in from abroad will be more expensive than hiring a Swedish resident.

There's some interesting developments on work immigration in Sweden. The current government, together with the Green Party, is proposing that anybody, from anywhere, can automatically get a two year work permit if they have employment from a Swedish company. The requirements are that the job be properly advertised within the EU as well and that the job be full-time and come with the union-agreed salary, benefits, job security and all other conditions Swedish employees already get. The two year work permit would be extended another two years if they're still employed, and permanent work residency be granted if they're still employed after four years. Note that especially the benefit requirement - which the unions will be sure to enforce fiercely - really precludes the use of this as a way to dump salaries or import low-wage manual work; taking someone in from abroad will be more expensive than hiring a Swedish resident.I find this very interesting. First, it acknowledges a reality that is often forgotten in all the frightened rhetoric about immigration: Most people do not want to leave their friends and relatives and move to a different city, never mind a different country - even if it might mean a better job, higher salary and better social safety net. When you leave your friends, relatives and co-workers, you're leaving your entire social and work network behind, and it's through those networks that most people find new jobs, work-related contacts and so on. Leaving that resource behind can often be an economic as well as social net loss even with a better job as incitement. A frequent complaint among expatriate workers is that their career suffers from the lack of networking and face time with people in their organization. It is, I think, not a coincidence that academics are one of the most mobile workforces in the world and also people with famously wide-ranging networks.

It's been a few years now since a number of former communist east-European countries joined the EU and the free labour market. And contrary to many people's fears and expectations, we did not get a massive influx of poor Poles, Slovaks or Romanians eager to take advantage of Sweden's labour market and social safety nets. In fact, it didn't amount to more than a trickle, and those that have come have been people we've in short supply of. Unless driven to it by destitution, severe persecution or violence, most people would just rather stay where they are. People willing to relocate to a different country (like me) are outliers, the exception to the rule. People willing to do so not just for a few years but perhaps for good are even rarer.

Second, this acknowledges that skilled people are a valuable resource, not a liability, and it's a resource that's growing scarcer as more societies climb the economic ladder. If you have the skills - academic, administrative or artisanal - to merit the attention of a foreign company despite the extra costs, hassle and uncertainty, then you're the kind of person to be in demand in many places in the world. As Japanese politicians and companies are coming to realize, a lack of skilled workers is deleterious to a society in the long run. Societies are increasingly in competition over such people and the last thing you want to do is discourage them from coming. Most will want to stay in their own home country, not relocate to some distant place with a foreign culture and different language. The problem is not to stem the flow of skilled immigrants as some people seem to believe, but to convince enough of them to come at all, open borders or not.

A welcome secondary effect is that the handling of refugees in Sweden - a clunky, inefficient and unfair system criticised from all political camps - will improve. Today the system is rather perversely set up so that people wait for years to find out if they will be granted refugee status or not, years in which they are not allowed to work. They have literally no choice but to live on public money since they are forbidden by law from supporting themselves - which of course leads to withering criticism from the far right and feeds xenophobic hatred of foreigners living on the public dole. And when a decision can take years, you have refugee families put down roots in Sweden, with new friends and relatives and with children growing up culturally Swedish rather than their ethnic origin. There are occasional cases where children born in Sweden, who speak only Swedish, are being deported with the rest of the family to a country they have never seen. This way, refugees can seek and find employment in Sweden, support themselves and avoid some of the alienation and destructive passivity of enforced non-work. And if they find a permanent job, then the refugee status question becomes moot as they'll get a work permit instead.

A last comment on the political ramifications: The proposition comes from the ruling coalition and from the Green Party together. The current opposition (way ahead in the polls by the way) is the Social Democrats, Sweden's largest party and traditionally the party in power; the Green Party; and the Communists. The last two are small, but there is no realistic way for the Social Democrats to regain a majority without the Green Party - the Communists are too small, and their recent backtracking into dogmatism makes them politically unsavoury to include in a coalition anyway. It means the current proposition has a majority in parliament, and barring a major upheaval the proposition will have a majority for preserving it no matter how the next election turns out. It looks like we're getting an immigration policy in line with reality at last. I wonder when Japan will draw some of the same conclusions.

Tuesday, March 25, 2008

Cup Noodle Museum

One of the great benefits of living in a large city is all the exhibitions, performances, galleries and museums that are readily available to anyone who wants to take an interest. On occasion we go to exhibitions we've heard about, other times we literally stumble upon something interesting on our walks. Last weeks cultural experience was the Momofuku Ando Instant Ramen Museum in Ikeda, Osaka.

One of the great benefits of living in a large city is all the exhibitions, performances, galleries and museums that are readily available to anyone who wants to take an interest. On occasion we go to exhibitions we've heard about, other times we literally stumble upon something interesting on our walks. Last weeks cultural experience was the Momofuku Ando Instant Ramen Museum in Ikeda, Osaka.Instant Ramen, for those that do not know, is wheat noodles cooked in a broth, then flash-fried in oil to dry them, resulting in a square or round noodle "cake". To eat them you simply pour hot water over them and wait for a couple of minutes. They are usually sold with packets of soup base and freeze-dried vegetables to make a complete meal. They come in flat, square packets; in plastic bowls; or in styrofoam cups. In Sweden I only ever saw the flat packets, while the bowls and cups seem to be most common here in Japan.

The inventor was Momofuku Ando, who perfected the idea of drying the noodles by flash-frying them in the 1950's. At first his company, Nissin, sold just the flat noodle packets. He once saw customers cook their noodles by putting them in a coffee mug rather than a bowl, and when he got a styrofoam cup during a flight he hit on the idea of selling the noodles in their own cup. In 1972, the Japanese Red Army took a hostage and occupied a building in the Asama mountains in Japan, in what was to become a ten-day stand-off with the police. Nissin rushed boxes of Cup Noodle to the site of the stand-off, and live national TV coverage of the drama streamed images of policemen gulping down the noodles to households all over the country. The success was complete, and something approaching the perfect fast food was born.

A staple food of students, night workers and busy singles, the savoury noodle soup leaves few people untouched when they encounter it, and opinions are frequently based as much on its perceived status and "naturalness" as on the food itself. They're a greasy, salty fast food packaged in wasteful plastic. But they're also amazingly convenient, inexpensive, long lasting, light and flavourful. You can store them for years, making them not only convenient as a back-up food for harried households, but also for stocking emergency supplies and for disaster relief. Today, a Japanese convenience store or supermarket will have many dozens of varieties of noodles, and there's even pots of hot water by the exit so you can buy your noodle cup and fill with hot water on the way out.

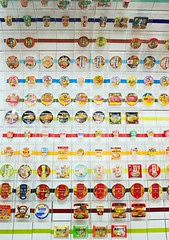

The Cup Noodle museum is in a residential area, right across the street from the Ando family home, and is surprisingly good. We half-expected it to be similar to other self-glorifying corporate museums but this museum clearly wants to reach beyond that level. It is a fairly big place, two floors, and full of visitors. There's a "wall of explanation" of course, but it - and the museum itself - focuses on the noodles and on its inventor, not the company. There's a whole wall of instant ramen products (it's a big wall, and getting crowded), and a set of display cases with ramen sold in other countries. There's a reconstruction of Ando's workshop and a small movie theater running a fun animated information film on making the noodles.

The centrepiece of the museum, however, is a "noodle factory" where you can mix your own Cup Noodle (there's even an area where people can make their own noodles from scratch, but that seems to be for pre-booked visitor groups only). You get an empty Cup Noodle cup, and start by decorating it at a table using the coloured pens. Then you go to the "Production Counter", where, first, you get the dried noodle placed in the cup, using a small manual version of the machine used in the real factory (the cup is put over the noodle 'puck', then turned around). You choose the soup base and four ingredients, much like you would at an ice-cream stand. The cup then gets lidded and shrink-wrapped, again using small versions of the real machines. Last, you get to put your cup in a nifty "air bag" to protect it until you get home.

Make your own Cup Noodle: When you've decorated your mug a museum guy will place a puck of dried noodles in it. Then choose, ice-cream stand-like, a soup flavour and four ingredients. Once the cup has been lidded and shrink-wrapped you place it in a inflatable bag for stylish transport home. We've still not opened ours, but I'm getting really curious how my mix turned out.

The last part of the museum is a café-style restaurant of sorts. It's packed with people; there was even a bouncer with a velvet rope regulating the flow of people. There are no waiters and no kitchen, of course; instead there's a wall of vending machines selling various versions of instant ramen. You have machines selling standard varieties; old-style noodles of previous eras; special versions produced only for the museum, and trial varieties that are not yet for sale in stores. We each had two kinds: Ritsuko had a classic curry-flavoured Cup Noodle and a Japan Airlines mini-ramen cup; I got an experimental bowl of tonkotsu ramen and a Japan Airlines soba cup. All were good, but I must say the ramen bowl was really excellent. It'll go on sale this spring so it is not the last time I ate it, I suspect.

Who goes to a museum like this? Judging from last Sunday it's school classes, parents with children and - surprisingly - many small groups of young, dressed-up women. Why? Don't ask me; I have no idea. Is a self-designed cup of instant noodles this springs must-have accessory? Is Cup Noodle considered a beauty product? Perhaps fashion-forward young Japanese girls simply love instant ramen as much as everyone else, and they have the free time to visit museums.

Sunday, March 16, 2008

Akan National Park

On the eastern side of Hokkaido, in the interior, lies three large lakes; lake Akan, Kussharo and Mashu, forming the Akan national park. And right in between those lakes lies the Kussharo Genya youth hostel, which happens to be run by a friend of Ritsuko's and his family.

You may expect a largely depopulated wilderness area akin to Sarek or Abisko national parks in Sweden, but that is not quite the case. Hokkaido is just too densely populated to really support large swaths of wilderness, and Akan is criss-crossed by roads and dotted with farms and fields, vacation homes, guest lodgings and other facilities. That said, the area is very beautiful, roads and all, and a welcome change from Osaka. In a way, the landscape reminds me a bit of northern Dalarna in Sweden, with its mountains and fields.

Of course, any similarity to Scandinavia is superficial. The Scandic mountain range is old and geologically inactive; Hokkaido, like most of Japan, is young and still very active, with hot springs, gas vents, earthquakes and calderas. New volcanic eruptions are possible and likely inevitable. The mountains and the three lakes are all the result of relatively recent seismic activity.

The trip to the area is by a small two-car, then one-car train (the kind called "rälsbuss", "rail bus" in Swedish). From what I understand the tourist high season is in summer, with swimming, canoeing, bicycling and general frolicking around the lakes; but even in the dead of winter was the train pretty much packed with people going to Akan or towards Shiretoko national park on the north-eastern tip of the island. JR also runs a couple of old-style tourist trains along the coast, a diesel train and an old steam train; on the way back we took the green-painted Norokko train, with wood stove-heated cars and amazing view of the coastline. Fun, and arguably more comfortable than the rather stuffed rail bus.

Our reason for choosing Akan wasn't the area itself, beautiful as it is, but that one of Ritsuko's friends runs a youth hostel there with his family. The Kussharo Genya hostel (more information on the Japanese site) is located right in the middle of the park, in between the three lakes. It is a fairly original octagonal design, with a round main room, major areas (kitchen, dining room, baths and so on) radiating out on the first floor, and the guest rooms spread out around the second. The place actually works more like a wilderness hotel than a normal hostel, offering various tours and guided sightseeing. Also unlike most normal hostels in Europe there is no guest kitchen but breakfast is included and you can order dinner. The dinner, by the way, is a multi-course menu I can't recommend warmly enough. Kazuhito is a trained chef from Osaka and worked in traditional Kyoto restaurants before he relocating in Sapporo and on to Akan to build the hostel. As a result the food, as you can imagine, is excellent.

The hostel interior, with its high-ceilinged main room. Yes, that is me relaxing after dinner in the center, and Ritsuko is in both the left and right images.

During winter there's plenty of cross-country skiing of course (the hostel will happily lend you gear); you can go for outdoor hot spring baths; and there's tours to the lakes and other scenic areas. But if you're lucky with the weather - and you're likely to at this time of year - the single most enjoyable thing you can do is simply to go for long walks in the snow-white sparkly landscape and soak in the hot-spring bath in the hostel. The area is criss-crossed with small, well-maintained roads and the nearest lake, Kussharo, is only a few kilometers away by foot. We went on a car tour to Mashu and Kussharo lakes the first day, but apart from that we simply spent our time enjoying the winter weather, not doing anything at all.

Lake Mashu. It's a caldera with steep cliffs and no natural beaches. And as it's a protected area no construction is allowed so there is no access to the lake itself; the closest you get is two view points around the lake.

Kussharo lake is easier to access than lake Mashu. It's still volcanic, though; the lack of ice near the shore is due to hot water and gases percolating up from beneath the sandy bottom around the beach. The swans evidently appreciate the warm water a great deal too.

The flights both from and to Osaka were near-full and the airport was crowded. The hotels in Abashiri were alve with people and when we booked the Aurora icebreaker tour three months earlier most trips were already sold out. The train to Akan was standing room only both coming and going. The hostel was just about fully booked, with a group of Australians, several single Japanese travellers (this is very common) and, well, us. lake Mashu had more tourist buses and their occupants than you can shake a stick at, and at the shore of lake Kussharo the main problem was to find a vantage point that wouldn't frame a fellow photographer when you tried to shoot the gathering birds.

And yet, many of the few shops and restaurants in the area were closed for winter or permanently. JR will apparently no longer run the train to Mashu station, stopping earlier on the line. I kind of wonder why the area doesn't seem to be able to live on the kind of visitor interest that evidently exists. This level of interest is probably as good as it gets. I suspect the train service and other businesses are still largely meant to support the local agricultural business, not tourism, and this reflects the state of the former industry rather than the latter.

A final observation at the airport: Two years ago, a Hokkaido manufacturer of cookies and pastries was caught cheating with best-before labelling on "Shiroi Koibito" cookies. Unlike many other companies, they reacted quickly and decisively, withdrawing the product until they'd completely revamped their business procedures. "Shiroi Koibito" vaulted into the public conciousness, and now the company can't produce enough to meet demand from Hokkaido tourists looking for omiyage. The airport had throngs of passengers roaming from store to store looking for them.

Fun trip. We'll be back; next time perhaps in summer. More pictures in my Akan photoset.

Tuesday, March 11, 2008

Pay to Work

GlobalTalk 21 has an enlightening post about election financing in Japan. As it turns out, candidates for major parties are expected to shoulder most of the election and campaign costs - tens of millions of yen - personally. As Okumura-san points out, this means that the parties have real problems actually finding willing candidates in all electoral districts; it also means it is very difficult for ordinary people to break into politics. You need to be independently wealthy or come from a political dynasty where most of the groundwork has already been done for you in order to stand as candidate.

GlobalTalk 21 has an enlightening post about election financing in Japan. As it turns out, candidates for major parties are expected to shoulder most of the election and campaign costs - tens of millions of yen - personally. As Okumura-san points out, this means that the parties have real problems actually finding willing candidates in all electoral districts; it also means it is very difficult for ordinary people to break into politics. You need to be independently wealthy or come from a political dynasty where most of the groundwork has already been done for you in order to stand as candidate.Another aspect, though: the candidates are effectively expected to pay for the privilege to stand election for a party. At first this looks preposterous; in what professional field would people be expected to finance their own salary and expenses for the privilege of working long hours for an organization? Well, academic research comes to mind, actually. It used to be that established researchers would receive a salary and most of their research funds from their university, supplemented by external funds for expensive equipment, travel and so on. Today external financing is increasingly the main or sole funding source for research projects, and I've lately even seen an ad for a research and teaching position at a Swedish university where the applicant is expected to not only bring their own research financing, but the funds for their own teaching salary as well.

The university is transformed from a long-term employer to little more than a research hotel offering its name (necessary for many applications), lab space and administrative services in exchange for a hefty cut - 40-50% is common - of the research grant. Good for the university, of course; they can attract researchers that bring in funds and prestige, and avoid having to keep unproductive people around for many years. They can quickly shift the focus of their research labs when new, exciting results vitalize a field of research and dump a field the moment it starts looking stagnant.

But as a result, researchers - especially the top talents that can attract large grants - have little attachment or loyalty to any university any more. It's quite common now to hear about research leaders that get recruited and leave their former "employer" mid-project, taking their funds, their post-docs and assistants along, and leave the university with an empty lab, expensive equipment, stranded students and some red faces. At times, the same name crops up again a year or two later as they leave their new university for still greener pastures elsewhere.

And longer term, of course, the question is to what degree these researchers and their projects really need a university any more. Lab and office space and management services can be had on the open market, and for quite a bit less than the large cut many universities take. You do need an affiliation to a research organization to be eligible for grant applications in many cases, but nothing says it needs to be a university, or that you physically need to be located at the organization. I could well imagine a private research institute branching out to offer affiliation to independent researchers for a small cut or yearly fee. he research group gets the necessary affiliation, and the institute gets some high-profile research to its name without the expense and headache of actually hosting it.

If we return to politics, the situation shares some similarities and there is a clear possibility of a similar dissolution of loyalty between lawmakers and their parties. More and more of pre- and post-election resources are tied to the politician personally, and come from sources other than their party. A party of course offers their name - political branding - and a party affiliation is often necessary to partake in the give-and-take of parliamentary work (you need party support for juicy positions, just like you need a research affiliate for grants), but again, there is no real reason to stay with one particular party at any cost. The more an election costs the less beholden is the candidate. A veteran lawmaker (or dynastic scion) comes with his own district-wide name recognition, his well-tested local organization and a stable cadre of financial donors (legal or not; improper political donations are a leading cause of indictments here). An established politician may in fact need his party quite a bit less than the party needs him.

Lawmakers do shop around in Japanese politics; a not inconsiderate number of lawmakers have switched parties, sometimes several times, during their careers. And you can argue that the same mechanism is at play among internal party factions in the LDP, with individuals changing their allegiance in return for a cabinet post or committee membership. This, by the way, happens very rarely in Sweden, as most election costs are borne by the parties, not the representative. As internal cohesion weakens and parties become little more than

Seen from that perspective, and disregarding their ideology, the tiny "People's New Party" or the one-man party of "New Party Daichi" could be seen not as failures but as a sign of possible things to come. These are tiny parties started by disaffected lawmakers in an effort to break free from the main parties. As political movements they are clearly failures, but as vehicles for their founders' political future they are not. With your own personal party you get most of the benefits of party membership with few of its disadvantages. And once in the city council, prefectural assembly or diet you can enter into more or less formal and long-lasting coalitions with other small parties to push a common agenda, or attach yourself lamprey-like to one of the major parties for an election cycle in return for committee influence.

This is highly improbable, I know, but in a way not very far from the current de-facto situation. For a number of representatives (at all levels of government) it would really just formalize their current ambiguous relationship with their party and make it easier for lawmakers with commonalities of interest to find each other across the party divides.

Sunday, March 9, 2008

Abashiri

Abashiri, with the river, the main road and the railroad tracks all running towards the sea. Lots more pictures in my Abashiri photoset.

Abashiri, with the river, the main road and the railroad tracks all running towards the sea. Lots more pictures in my Abashiri photoset.Abashiri lies on the northern coast of Hokkaido, along the sea of Okhotsk. As a town it doesn't have all that much to recommend itself. It is about 40000 people strung out along a river valley ending in an industrial area and fishing port out by the sea. Its claim to fame is less than illustrious; Abashiri is mostly known as the site for Japans most famous old high-security prison, and the current maximum-security prison still gives Abashiri occasional media exposure on the news and in crime dramas. The prison at one end of town and the port on the other are the traditional main industries in this city.

But Abashiri is also a travel nexus; it sits on the northern coast facing Russia, with a nearby busy airport and with local railroads that all converge on the town. Any traveler to Akan or Shiretoko national parks will be quite likely to pass through this area. And while the city won't win any beauty contests, there's still the beautiful scenery, the prison museum, the sea tours and the local brewery (making actual Altbier none the less) to keep you happily occupied.

And indeed, there were many tourists around, from Japan and from abroad. Lots of Chinese and Australians, with quite a few other east and south asians sprinkled in (a surprising number of Indians, for instance). I gather there are some direct flights to the airport from those areas for people coming to Hokkaido for the national parks or for the skiing. In fact, the town feels almost like two towns overlaid on one another. One town is a sleepy backwater catering to the traditional industries; local eateries, shops and small businesses supporting the fishing fleet, many of which seem closed for winter (or closed permanently perhaps). The other town is a fairly lively tourist destination with shops and restaurants catering to visitors, and they seemed to be flourishing. Sunday we went to a kaiten-sushi place catering to the locals. Very good, but being a sunday evening there were very few people; perhaps another four guests apart from us, all locals. At the brewery pub and restaurant down the road you could hear a dozen languages spoken and we had to wait for ten minutes for a table. I can't help but wonder if not the future of this city is not going to be connected more to the vagaries of holiday travel trends, rather than the price and availability of fish.

We stayed the first night in a ryokan overlooking the port. The place itself was nice enough - an older building with small traditional tatami rooms, worn but clean - but the reason we chose it is the crab dinner it offers. And it didn't dissapoint: a whole King crab for two people, quickly pressure-cooked in sake and served with various side dishes. It was wonderful; juicy and soft with a truly intense flavour. I don't have a thing for crab the way many Japanese do but this was truly great. The only complaint would be that one whole animal really is too much for two people.

Crab dinner. Delicious. Also, if you're in Hokkaido you need to eat Hokkaido-style ramen; at least, you do if ramen happens to be a favourite food. This is miso ramen, but with some of the greasy tonkotsu soup added for a fuller body.

The next morning we went on a "floating ice tour" on an icebreaker. The north coast is the only place in Japan you get pack ice in the winter. It is a major drawback for the fishing industry; many boats are simply laid up for winter since they can't work in the ice. But the towns along the coast have turned this problem into a major tourist draw, with ice tours, exhibitions and museums. The icebreaker Aurora (they actually have two ships running together) takes tourists out to the ice for photography and general sightseeing. It's very popular - you need to book beforehand - and understandably so, as the view really is quite beautiful, with an endless expanse of ice and sky meating at infinity.

As it happens, the port was also the site of the Abashiri snow festival, with a collection of ice and snow sculptures, and even a snow labyrinth and stage. We went there at night to see if we couldn't get some pictures without a lot of other people around; of course we weren't the only people with that idea.

The Abashiri snow festival. From upper left, Moomin characters; Owl family with Ritsuko; an ice goose; and Ritsuko standing very still among the food stalls for a long-exposure shot.

Abashiri Prison Museum

The prison has been a major feature of this town since the late 1800's; in fact the prison is the reason Abashiri became a city rather than stay another poor fishing village. It's easy to see why a prison would be located here; with no roads, few or no people rough terrain and inhospitable climate the chances of escaping must have been remote indeed. The old prison was finally decommissioned some years ago and replaced with a modern maximum-security facility, but some of the older buildings were moved to a nearby area to form an open-air prison museum.

This museum was one of the highlights of this trip. It's fairly large, with buildings from every era of the prison scattered about on a pleasant wooded hillside. Seeing the sometimes unheated cells in winter really brings home just what a hellish existence was offered to the inmates at one time, and indeed, many prisoners died from disease, exposure or malnutrition.

A cell block, and a prison hut as it looked at the start of the prison. More images at my prison photoset

The second night was spent in a standard "business hotel" next to the station; the prison made itself known here again with prominent signs forbidding any guests with tattoos or cut fingers from using the baths. And in the morning we left Abashiri for Akan national park.

Hokkaido

As I previously wrote, we left on a trip to Hokkaido a few weeks ago. But the droves of pictures I took combined with a somewhat busy schedule at work has put off posting about the trip until now.

I'm going to split this up into a few parts since the trip really was thematically different; in the grand holiday traditions of this country we did not go to just one place. We went to Abashiri on the northern coast where we stayed for two nights - in two different hotels, no less - followed by two nights in a youth hostel in Akan national park.

So, why would you go to northern Hokkaido in mid-winter rather than, say, balmy Okinawa? And not even to Sapporo (the main city) either, but a small town like Abashiri? Mostly we wanted to go somewhere a little different than the usual holiday destinations. Ritsuko has a couple of friends up there; also, I've been pining for real winter weather for a while (something in short supply in Osaka).

It turns out winter is actually a very good time of year for Hokkaido. There's lots of snow and it isn't all that cold; the average in February is similar to Stockholm at about -7 degrees with an average daytime high of about -3 degrees. And Abashiri is fairly southerly - about as far north as Venice or Cannes - so we get long, bright winter days with a wonderfully crisp, clear winter sun in an intensely blue sky.

Next up: Abashiri, home of the nonfree!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)